Virginia-based photographer Matt Eich has spent the last decade developing a documentary photography practice that blurs spaces and genres. Picturing his family as well as others throughout the United States, he's built an extensive body of work that speaks about memory, belonging, identity, and collective consciousness; themes that are even more salient in today's sociopolitical climate. Candid, he shares some of the lessons he learned along the way, about balance, the creative process, the tensions between personal and journalistic endeavours and what the medium affords him.

Published September 28, 2018

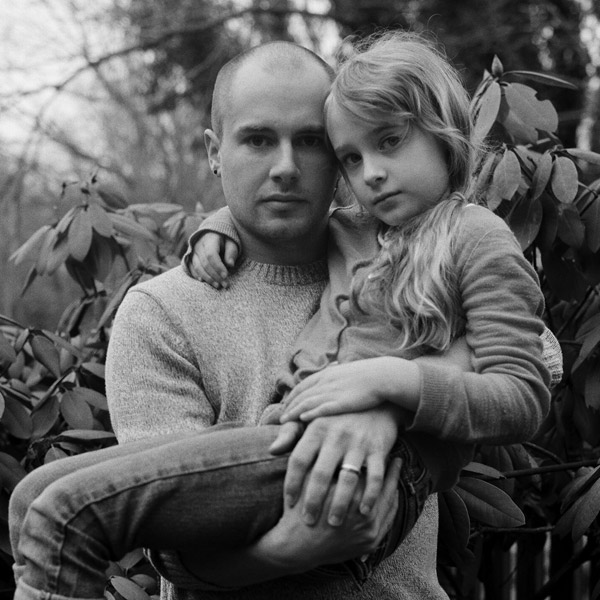

Photos by Matt Eich, 2009 Bright Spark Award Winner

LBR. You teach, you work on very personal and intimate photo projects, and you also cover assignments, what has been your strategy for finding balance so far?

ME. Whenever I think about balance, I always go back to something one of my professor said to me in undergrad. He had two kids, was teaching and still doing personal work –much the same situation I’m now in. It seemed like he had everything figured out. I asked him how he balanced it all, and is response stuck with me. Essentially he said that there’s no such things as balance, it’s an illusion. There’s always something that suffers and it’s up to you to have the wisdom to decide what suffers at any given time. If you’re gone making work for extended period of time, then your personal life, your relationships will suffer. On the other hand, your personal work might suffer if you’re spending a lot of time teaching or because your family’s needs outweigh that of your project or if someone calls and says I need you to do this assignment by 5pm. And so on.

I try to keep that in mind and make sure that my priorities are in check. The way I view it is that there’s this kind of triage where family is the most important. If I need to be home for a birthday or anything else, than everything falls by the wayside. The next is what provides stability for the family financially or otherwise. Teaching requires a lot of my time at the moment, because it is still very new for me. My hope is that it will bring stability in the future, but for now, it’s mostly causing further chaos. Assignments also account for a portion of my income so I have to prioritize those. Hence, the personal work often gets shuffled to the back burner. Even though my brain is constantly thinking about what I need to do next in that regards.

From "Carry Me Ohio"

LBR. And what might those next steps be?

ME. I’m working on a series of four books, “The Invisible Yoke”. The first “Carry Me Ohio” came out in 2016 and the second “Sin & Salvation” is slated to be released in October. It goes to press this week while I’m in Oregon for the opening of “I Love You, I’m Leaving” at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland. Everything needs to be finalized before I leave to teach tomorrow… And, when I come back, I’m installing work at Blue Ridge Community College while also starting the hustle to promote the book, trying to find publications that will feature excerpts or review it. Much of this has nothing to do with supporting the family or making money, but about getting this body of work out there, which is why we do it.

From "Sin and Salvation in Baptist Town"

LBR. Since you brought up “The Invisible Yoke”, how did you conceive of this four part opus? Did you know from the outset that it would be a tetralogy or did that idea emerge has you were making the photographs?

ME. I’m definitely not a concept-first photographer. I know some people come up with an idea and execute it without deviating from it much. But, for me, photography is more of a stumbling through the dark and seeing what I manage to gather along the way. Then through many edits, thinking and listening to the pictures figuring out how they connect to one another; what they are saying.

Take for instance the second chapter, “Sin & Salvation”. I was initially sent on assignment to Mississippi and within the first three days, I was hooked. So I got the editor to send me back for awhile. I used that time to put down some roots in the community, but I still didn’t know what I was doing exactly. I just knew that I needed to be there, listening, photographing and spending as much time as possible before gaining any awareness of what the work was actually about.

From "Seven Cities"

The way that “The Invisible Yoke” emerged conceptually is that I had this established body of work in Ohio, was beginning this new one in Mississippi and as I started editing the pictures, I realized there were echoes of the same themes running through them. Essentially, they’re both dealing with disenfranchised factions in our country. Poor white folks in Ohio in the wake of industry leaving. Poor Black folks in Mississippi where the legacy of racism and segregation shape opportunities.

And with both of these cases, I’m dealing with communities that are not mine. So I started this third part, “The Seven Cities” about Virginia, specifically the area where I grew up and where I’m raising my kids. I thought of it as a trilogy that would, taken as whole make a larger statement about America. When I assembled the photos within a series of three, I was left wanting more. I saw the gaps in the structure, the house that I was building, and that there was a slew of images that I thought of as orphan, that didn’t have a home. They are outtakes from assignments or from projects that didn’t lift off. They felt like they could become their own book. I gathered them into “We, the Free.” While the first three are bounded by regional geography, the last is about the country at large. The goal is to have the final volume drop before the next Presidential election. The whole should be a pretty clear statement about how I see our country at this juncture, what’s led us here and the questions I have about who we are and where we are going?

From "We The Free"

LBR. Speaking of the current socio political climate in the United States, and as someone who lives and works in Charlottesville, Virginia, what do you make of the events that unfolded at last year’s Unite the Right rally?

ME. I’m still trying to unpack that. I had planned to go and photograph on my own, most likely with medium format black and white film. And then two days before, I got an assignment to cover it from The New York Times. I was a little torn, but felt it wouldn’t hurt to have support if something went wrong and an outlet for the images.

I thought it was going to be the average group A on one side, group B on the other with barricades and police in between with a lot of yelling. Within the first couple of hours of that day, it became clear that it would be different. The cops were hanging back, watching people beat each other. It caught a lot of us by surprise. While a lot of the perpetrators of violence were from out of town, they were also invited to commit violence here… and that’s something we need to deal with.

It took me weeks afterwards to feel like I was putting my head back together a little, sleeping right, eating right. It was disconcerting, having traveled around the country feeling those tensions over the past 10 years, to see it rear its ugly head right in my backyard.

Fast-forward a year later, no one really cares anymore. The Unite the Right rally was a flop in DC. Partly because the trolls that came out from behind their computers in Charlottesville realized the consequences of being identified; some lost their jobs, a few are still being prosecuted. That’s good, in a way. But, they’re still there. They’re just back in hiding, behind their computer screens, waiting for the right moment to step out again.

The Unite the Right Rally, and counter protests in Charlottesville, Virginia on Saturday, August 12, 2017.

LBR. In terms of photographic practice, you hinted at the tension between being there to cover the event for a major publication and going to make work for your own project. How do you reconcile the need of one with the vision you have for the other?

ME. Really early on when I was interning at newspaper, I understood that editors have expectations for every assignment. Some are very clear, which helps guide you, but can be limiting. Others are more vague, telling you to ‘see what you see, feel what you feel’. That’s freeing, but doesn’t give me much structure or direction to work with. So, I always try to cover the basics and then from that point, make what I want to make, and hopefully surprise myself along the way by making pictures that I didn’t expect.

With the Unite the Right rally, I was thinking less about what the editor might want, but about what was unfolding in front of me. Still, while I was initially told to file by the end of day, because it turned out to be a much bigger news story than anyone anticipated I was asked for pictures immediately. Which meant I had to leave the scene, drive across town, send the photographs. As soon as I got home, I got a call from another photographer telling me to come back because someone drove a car through the crowd. That was an instance when I changed my working for preferences for the editor’s need and I shouldn’t have. I should have said: ‘things are still unfolding, you’ll get the pictures later’.

From "I Love You, I'm Leaving"

LBR. As you’re observing this national unraveling and reflecting on it through “The Invisible Yoke”, you’re also working this project about your family “I Love You, I’m Leaving”. Where does it fit within this triad you mentioned earlier? It’s work, yet it’s also about spending time with your loved ones. What happens when you mix the two?

ME. I think of it as two sides of the same coin. When I go into other communities, I’m looking for the same level of respect and intimacy that I would give my own family, photographically speaking. That’s the bar I’ve set for myself: how can I photograph these strangers with the same love and care that I would my wife, my kids, my parents. If I’m not willing to subject myself and my relatives to that same level of scrutiny and vulnerability, what right do I have to ask that of anybody else?

That’s one part of the answer. The other part is simply the compulsion. I realized that my work hinges on these themes of memory, family, community and country. The memory aspect goes back to my childhood and watching my grandmother losing herself to Alzheimer’s disease. In that instance, photography became a way to store memories, which seemed very fragile. If I never got another call for an assignment and dropped off the photo community radar, I would still be here making pictures of the people that I loved.

In fact, I’ve been photographing my family since I was a kid. It became really serious when I was in college, and found out that my wife and I were going to have a baby. I was 19 at the time and had documented our relationship before, but this felt important in a whole new way. We were starting a new family. These early years became a short film, “Love in the First Person”. And though I was still taking pictures of them, I pushed that aspect of my work aside to focus on the stories that make up “The Invisible Yoke”. That is until grad school, when something happened with my parents that reoriented my attention and made me want to understand the complex relationships that continue to evolve between us. I was watching my parent’s marriage end and thinking what it meant for mine, for my kids.

From "Sin and Salvation in Baptist Town"

From "I Love You, I'm Leaving"

LBR. I want to go back to what you said about your work dealing with family, community and country, which are essentially different levels of belonging and identity. What can photography reveal about these sentiments which are largely invisible and even difficult to articulate?

ME. “The Invisible Yoke” largely deals with the collective consciousness as Americans; what we choose to remember and to forget. We very easily forget the breadth of slavery. Or if you ask the average American, if the nation is guilty of genocide, they would say ‘no.’ When in fact we did wipe out a Native population, not so long ago. But we conveniently choose to forget. One of the things that photography is capable of is reminding people. With the series of four books, I’m trying to unpack that collective memory. That’s what connects us. It’s the yoke.

What you might also be asking here, is how I’m using photography to figure out where I belong. I grew up an introverted kid in a small rural area and never really felt like I belonged in the family unit I was raised in, or in the community. Hence, I was deeply curious about the lives of other people. At best, photography gives me a sense of belonging to the photo community, in which I found the sense of family that had been elusive to me.

While a cliché, this idea that the ‘camera is a passport’, it’s partly true. It gave me the opportunity to connect with the lives of people who I otherwise wouldn’t have met and through that, hopefully gain empathy for their experiences. That said, I do feel it’s dangerous to think of photography as a way to accumulate knowledge. Photography is, for me, more about emotional resonance and connection.

Matt Eich (b. Richmond, Virginia, 1986) is a photographic essayist working on long-form projects related to memory, family, community, and the American condition. His projects have received support from an Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship, a VMFA Professional Visual Arts Fellowship, and two Getty Images Grants for Editorial Photography. Eich was an artist in residence at Light Work in 2013 and is invited to a Robert Rauschenberg Residency in 2019. He teaches photography at The George Washington University in Washington, DC. Matt accepts commissions and resides in Charlottesville, Virginia with his family.

Laurence Butet-Roch, a member of the Boreal Collective and Muse Projects, is a freelance writer, photo editor, photographer and educator based in Toronto, Canada committed to encouraging critical visual thinking. Her words have appeared in the British Journal of Photography, The New York Times Lens Blog, TIME Lightbox, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Polka Magazine, PhotoLife, BlackFlash and Point of View. She is the editor of Flash Forward Flash Back.