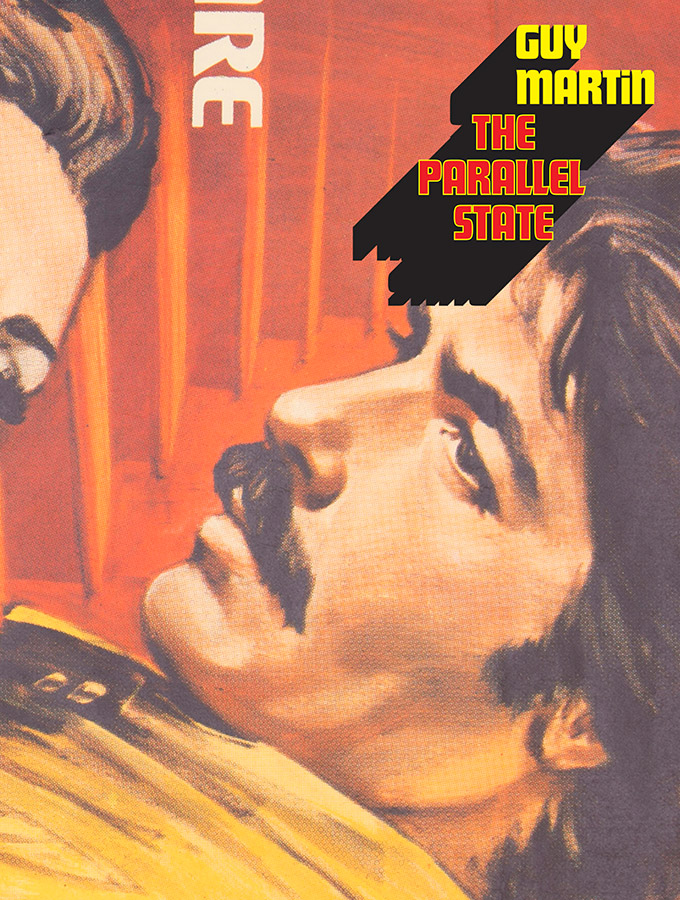

Published in December, "The Parallel State", by Guy Martin, is both a layered study of the intersection of fantasy and reality in Turkish society, and a meditation on how documentary photography operates informed by years of covering conflicts and revolutions. Frank and self-reflective, the British photographer shares how his thoughts on photojournalism have evolved since his début in the field, how the different pieces of a puzzle come together, and which moments and colleagues have been influential in his practice.

Published March 1, 2019

Photos by Guy Martin, 2007 and 2011 Flash Forward Winner

LBR. How does someone whose career was grounded in real events, come to do a project that intertwines reality and fiction?

GM. I feel it is my work as a photojournalist that has led me here. By my mid-twenties, I was working for the clients I had always dreamed of as a student. I was covering the Arab revolutions that were waged by people the same age as me, using technologies I had come of age with, but with vastly different purposes. In essence, I thought I had a connection, however small, to the events unfolding in North Africa in the early spring of 2011. At the time, a huge reason why I wanted to witness those events was because I wanted to emulate my photographic heroes. I believed that what made a good photojournalist rested in being brave, in being able to withstand seeing violence and handle everyday threats to your life. Or so I thought until that day in April 2011 when I was injured, and Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros died.

In hindsight, my relationship with photography was the wrong way around. Photography was using me, I wasn’t using photography. All the different intoxicating parts of being a photojournalist—the travel, the danger, the hard environments, the camaraderie, the expectations—led me to take a certain type of images when really, I was witnessing something much more complex about performance that I was having a hard time to articulate. Tim and I talked about it. I wanted to look for less tangible, less didactic pictures but didn’t know how to do that.

Having a set of injuries that were so bad that it takes you eighteen months to learn to walk again, that required a number of operations back in the UK, where I’m from, gave me time to reflect on what I was doing as well as whether I wanted to keep on doing it given the costs, the risks and the stress it placed on my loved one. The last thing I wanted to do was put myself in danger again. Once you remove risk-taking out of the equation that determines the photos you make, then you have to concentrate much more on what the message you’re trying to communicate is. And, what I wanted to talk about involved this performance I had witnessed, how people played in front of the camera, the way that subconsciously, or not, what we see on the television informs how we speak, behave and look outwards into the world.

In other words, I wanted to rebalance the relationship I had with photography. To be the one using it, rather than the other way around. I moved to Istanbul because I still had unanswered questions and this gnawing sense that there was an opportunity there for me to say something meaningful.

LBR. In Istanbul, what drew you to the soap operas?

GM. Back then, In 2012, Turkey was a good news story. It was seen as pro-Western. One of the exports that contributed to projecting this image was their soap operas. They were the most watched soaps in the world due to their reach across the Muslim world, from the Balkans to Indonesia. So, I reached out to a tv controller at Canal D, one of the producers.

It was a great way for me to get back into photography. It was safe. It gave me the freedom to experiment with ideas and to fail. They would shoot the same scenes from five different angles for five hours, so I had time to figure out what it was I wanted to frame. Eventually, rather than shoot in a “behind-the-scene” tradition with the staff and decor visible, I would stand next to the cameraman and in the seconds just before and after the director said “cut”, I would take a few pictures. The actors were then still in this grey zone of portraying their character. This was what the cameraman was recording, and thus what the audience would be seeing. It enabled me to make a comment about television and reality. I was immersed in what Turkey wanted to portray itself as.

One of the most popular soap opera was called Noor, which translated from Turkish means “bright light”. The plotline generally revolved around a poor country girl from the East lacking manners and decorum that would come to Istanbul, this city of dream and wealth and entrap a beautiful rich white-looking Turk, creating chaos in his entourage.

LBR. How did a soap opera like Noor shape Turkey’s perception of itself and influence how people in the country were behaving?

GM. More than anything, it sidetracked viewers. Soap operas were veiling what was going on across the country. They weren’t touching on any real political issues because they are in essence dreammakers and are such a massive soft power tool. Plus, they reflected the version of Turkey that we wanted to believe in. I heard a former British Ambassador say that the West always wanted its version of Turkey to be the truth; not only that but we acted towards it as if it were, when really there were fierce tectonic battles between conservative and secular ideologies.

Now that the winds have changed, they’ve become much darker, much more like Homeland. It’s about fighting ISIS, fighting the terrorist responsible for the 2016 attempted coup d’état as well as the Kurdish separatists in the Southeast of the country.

LBR. The Parallel State doesn’t only feature stills from soap opera sets, but also images from political events happening in the country. When did the two come together?

GM. In the summer of 2013, when the Gezi Park protests, which called for more transparency and openness in political processes, were happening. Initially, I didn’t want to cover them. I was happy to avoid them and continue on with the soap operas. But, when I began to see the coverage, it felt as it often does, it lacked the nuance I had hoped for. And, when I did go, I realized that the way it was unfolding wasn’t like in the rest of the Arab world. It was unique to Turkey.

So I made the conscious decision to work differently, more deliberately. I took two or three flashgun lights with me to control the lighting more, to focus on the ‘cinematic’ qualities of the protests. I worked slower. Looking for something quieter, stiller than the usual iconic protest imagery. The people in Istanbul recognize the role of the narrative the media spins in the success of a movement. They understood their role, how to perform it, when to throw a rock, when not to, the flags to wave, the slogans to shout.

Early on, I saw this young guy lying in the grass. His friend noticed me and ripped the young man’s shirt in front of me and displayed him that way for me. Had I been working on an assignment, I wouldn’t have taken the picture because it wouldn’t have been ethical to do so. However, because I was now thinking about performance, I clicked the shutter. That image is very similar, in the gestures, in the angle, the framing, to the one from a soap opera that shows a dead girl on the ground. Putting the two next to each other made me realize that there’s was something strong I could say about how on-screen drama and real-life drama intersect by mixing them.

LBR. What’s more important for you: that the viewer eventually be able to discern which images are from soap opera sets and which are from reality if they learn how to read the pictures or for the two to completely blend together?

GM. Either/Or really. I’m interested in them thinking about the different levels of power and how it manifests itself. Spending time in Turkey, I eventually started to understand an expression that was very common there: “the parallel state”. They are obsessed by this idea that the country is being ruled from the outside. After World War II, NATO made sure they had sleeper cells there that could rise up in case communism took hold in the region. It never did, so they remained blended into the fabric of the society. Since, it has become a constant belief, that outsiders representing different ideologies have a hand in the national affairs. And of course, during elections, politicians hammer on this fear. Hence, the protesters in Gezi Park, they were portrayed as agents funded by Soros, embolden by the likes of The New York Times or TIME magazine.

LBR. That rings a bell…

GM. Many of the issues Turkey was grappling with then, the US, the UK and other European countries are now grappling with. We’re now used to hearing the term “fake news”, having the media being called “the enemy”. Erdogan has been playing that tune for the past six-seven years…

LBR. How did you know that you had all the pieces of the puzzle? That it was time to make a sense of all these fragments you collected that includes movie posters, screenshots of texts, as well as the images you’ve made?

GM. When the attempted coup d’état happened in July 2016, when the real-life parallel state tried to take power. Now reality defied fiction.

LBR. I’m sure you didn’t process all of these ideas alone, who helped you push your thinking forward as you worked on this project?

GM. Donald Weber was a good person to speak to because he also grappled with how visual representation, non-fiction and fiction come together. We both wanted more from the images we were producing. I’ve always been quite concerned about the impact my work was making. I often wondered whether the reports I produced from say Egypt really touch people like my family; after all, it was so exotic, so removed from their experience. That’s also a reason why I was compelled to focus on soap operas. It felt like a way to get the attention of a new audience and then gradually lead them into a much more complex narrative.

Going back to Don, I was also inspired by his series Interrogations because it speaks about power and its misuses. Finding ways to visualize power opens another way of talking about our work. The images I was making before, they say nothing about power. They talk about the victims, the end results, but not the causes.

Carolyn Drake and Guy Tillim also helped tease out the themes, the issues, the parallels, the connections between the different set of images I had. For instance, Carolyn reminded me that the women from the soap opera sets I was photographing were challenging the ideas we have of what an Eastern women does or should look like.

LBR. Now that you’re back in England, and that the book is published, where’s your mind at?

GM. In The Parallel State, there’s a short fiction called “The Giant that Sleeps Underneath Istanbul” by Pelin Turgot who used to be TIME Magazine’s Istanbul bureau chief. She felt that the book was making a strong case for how Turkey has always been looking for its identity, shifting between Western ideals, nostalgic ottomanism, conservatism and so on. We’re in the midst of a similar identity quest in the UK right now. There’s a lot of anger, especially for the politicians, that comes from a very deep place, from decades ago, when people felt that they were losing a sense of self. I’d like to draw from my experience in the Middle East and make something that is less about Brexit and more about this search for identity.

Guy Martin comes from England’s windswept Cornish coast and graduated with a first class B.A(HONS) in Documentary Photography from the University of Wales, Newport in 2006. Inspired by regions that are in periods of transition, he worked in Southern Russia, the Caucasus, Georgia, Turkey, Northern Iraq and, starting in January 2011 covered the revolutions sweeping through the Middle East and North Africa.

His work has appeared in the Guardian, Observer, Sunday Times, The Daily Telegraph, Der Spiegel, D Magazine, FADER Magazine, Monocle Magazine, Huck Magazine, The British Journal of Photography, ARTWORLD, The NewStatesman, The Wall Street Journal and Time. In 2011 he became a member of the esteemed photographic agency Panos as well as an associate lecturer in Press and Editorial Photography at the University of Falmouth, UK.

Laurence Butet-Roch, a member of the Boreal Collective and Muse Projects, is a freelance writer, photo editor, photographer and educator based in Toronto, Canada committed to encouraging critical visual thinking. Her words have appeared in the British Journal of Photography, The New York Times Lens Blog, TIME Lightbox, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Polka Magazine, PhotoLife, BlackFlash and Point of View. She is the editor of Flash Forward Flash Back.