LBR. The article “You Have to Be a Good ShapeShifter” that Bradley Secker contributed to the Everyday Project Re-Pictures series, brought to the fore some of the aspects of LGBTQ+ reporting that we seldom think twice about. I was hoping to continue the discussion by thinking further about the visual tropes used by photographers who cover LGBTQ+ communities. What do you feel those are?

DV. When I started photographing trans women in Latin America in 2012 for A Light Inside, most images I saw in mainstream media focused on sex work. Of course, the fact that many trans women are relegated to sex work is a large part of their life experience, but it’s not the only part. I chose to focus elsewhere because I thought it was important to show what we don’t often see in the narratives about trans women, such as their daily lives, their friendships, their partners, hanging out together, playing volleyball, cooking, etc. I thought that doing so would create a more layered understanding of trans women. That being said, sex work is a big part of their lives and relates to why many of them face health issues, lack of employment opportunity, as well as persistent violence and abuse. I didn’t want to ignore it, but I had to find other ways to touch on those issues without clearly showing sex work in every single picture. It’s a constant balance. My work doesn’t break all stereotypes, of course, but it’s something that I constantly ask myself and continue to reevaluate.

JTD. While making the project about older transgender and gender nonconforming people, To Survive on this Shore, I intentionally avoided focusing on the celebrity culture that was in vogue at the moment (i.e. Caitlyn Jenner) and chose instead to focus on individuals’ “everyday experiences”. In the interview specifically, I tried to allude to the complexities of each person’s identity and experience — that is, to speak of the struggles, of course, but also to show the joys, the triumphs, and the strengths. My goal was to paint as authentic and complex a picture of each person as I could instead of just focusing on the struggles transgender people face. At the same time, I didn’t want to sugarcoat the experience and imply that once someone transitions everything is wonderful and amazing.

It was also very important to me to focus on older adults (over age 50). Our culture at large is very youth-focused. I wanted to record the history of people who, in many ways, paved the road to where we are now and who have complicated and dynamic identities that are often underrepresented.

JN. One thing that I’ve found difficult about being a queer photographer working on queer stories is that even if and when I’m trying to present a story that is complex and rich, what editors seem to be interested in is often the most conflict-heavy part of a project, or they reduce it to its simplest storylines, making it hard to find a home for a nuanced pieces on a topic editors felt had been done before. I pitched work from the project This is How the Heart Beats: East Africa’s LGBTQ Refugees — about the largely unreported topic of LGBTQ refugees — to Harper’s in conjunction with the writer I had partnered with on the project, Jacob Kushner. The editor replied that it was “too soon for Harper’s to return to the subject of homophobia in Africa right now” as the magazine had published a film review three years prior, and a feature two years before that (totaling two pieces in five years).

DV. Makes my blood boil.

Sweet Love, a transgender woman, poses for a portrait in the bedroom of the Children of the Sun safe house with her partner Kenneth, with whom she has been in a relationship for two years, according to the two of them. Sweet Love co-runs the organization Children of the Sun, which provides shelter for young LGBTQ people in Kampala. Photo by Jake Naughton from "This is How the Heart Beats: East Africa's LGBTQ Refugees".

The dance floor at Ram, a bar in Kampala which hosts LGBTQ nights on Sundays and had become the de facto gay bar in the city. It was the only openly LGBTQ space in the country, but it was shut down a few months after this photo was taken, leaving the LGBTQ community there without a dedicated bar where they can go out and be themselves. Photo by Jake Naughton from "This is How the Heart Beats: East Africa's LGBTQ Refugees".

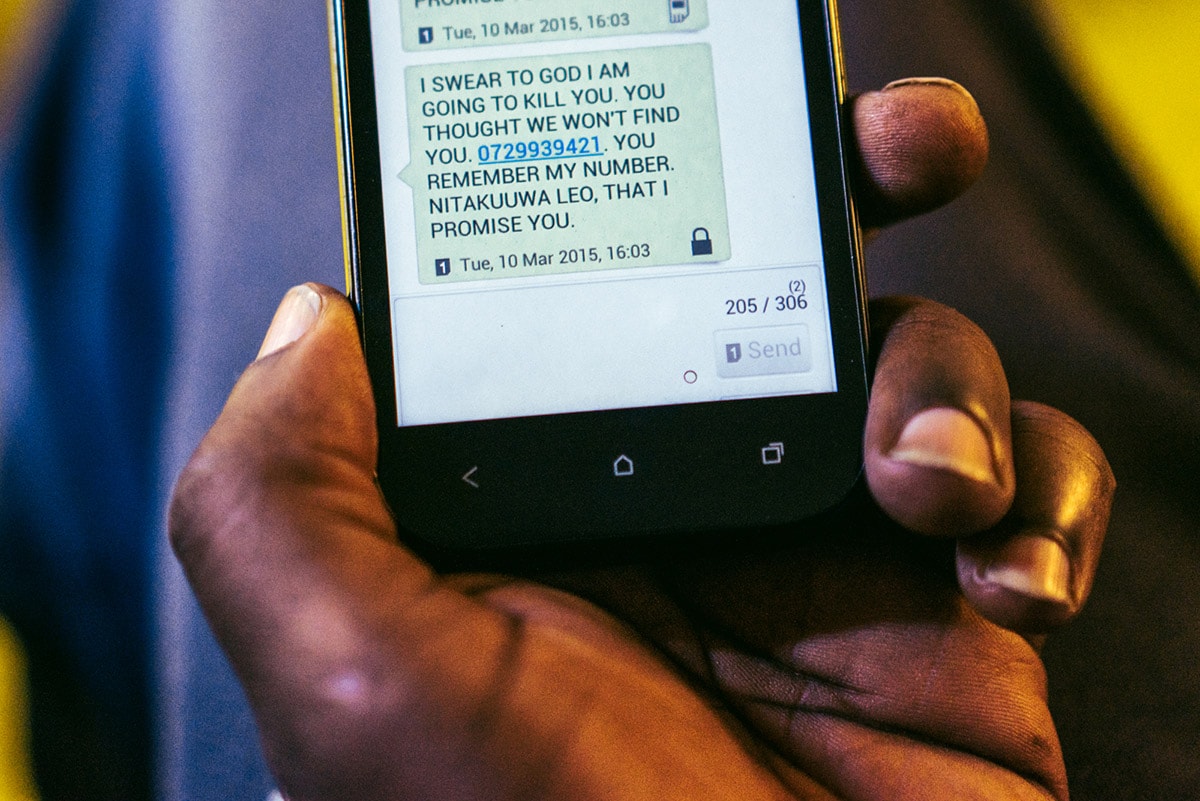

A text message a gay refugee from Uganda received from an unknown number soon after he arrived in Kenya. The sender threatened to kill him that same day, and so he went into hiding. Because he was unsure who sent the message, he lived in constant fear. He has since been resettled in the United States. Photo by Jake Naughton from "This is How the Heart Beats: East Africa's LGBTQ Refugees".

The reality is, most of the editors are not queer nor trans, so they have little to no knowledge of what I’m telling them about. They have no idea of what real is, of the nuances.

AT. That’s true of many issues. Just recently, there was a story in a major publication about Detroit, which my friend from the city and her friends felt looked like ghetto porn. I bring that up, because the photographer and writer were not for Detroit. The reality is, most of the editors are not queer nor trans, so they have little to no knowledge of what I’m telling them about. They have no idea of what real is, of the nuances.

JTD. This makes me think of two things. One is the significance of being part of the community you’re photographing. It’s something that I think a lot about in my work. In many ways I’m part of the communities I photograph, but, especially in To Survive on This Shore, I crossed lines around race, class, age, and socioeconomic status. I was very mindful of this while making that work. That said, to the general public, I’m an insider, because they assume that the LGBTQ community is one big unified community. Which it isn’t.

Secondly, it also makes me think about my ongoing body of work, Every Breath We Drew, begun in 2011, which engages with issues of sexuality, masculinity, and queerness in more complicated and fluid ways than we usually see represented in the mainstream. When I show that work, people tend to reduce it to ‘these are all LGBTQ people’ or ‘these are all transgender people’. It’s so hard to make work that is more than simply illustrating a singular identity. For instance, I have a lot of self-portraits, and I can’t tell you how many writers only focus on my body in their reviews when that’s not the only, or even primary, issue in my work. It’s an interesting challenge to make work from a queer point of view without being reduced to being “only” a queer artist.

Dee Dee Ngozi, 55, Atlanta, GA. To Survive On This Shore, 2016. Photo by Jess T. Dugan from "To Survive on This Shore".

Tony, 67, San Diego, CA. To Survive On This Shore, 2016. Photo by Jess T. Dugan from "To Survive on This Shore".

BS. I’ve also found that a lot of the coverage that I see lacks nuance. They either want stories where the people are quite victimized — especially when tackling the issue of LGBTQ asylum seekers and refugees— or they’re leaning towards a very sexualized imagery, like a couple kissing or naked; anything that clearly shows that they’re trans, lesbian, gay, bisexual.

AT. Indeed, when people are photographing trans women, they often show them putting on makeup, getting dressed or undressed. People have said about my photos: ‘I don’t know they’re trans’. Right. That’s great. That’s the point. And in that context, trans men are left almost completely out of the picture. Perhaps because people can’t visualize it easily. After all, they’re not putting on makeup.

Related to your experience Jake, I pitched a major publication part of Transcending Self, which I’ve been working on for five years, and they told me that they had just one their ‘gender issue’ for the year. As if we can only report on gender once a year.

BS. I’ve had that with gay magazines as well, to be honest. They would tell me that they’d done their international focus for the year. That’s even more depressing because it’s supposed to be about the community by the community for the community. And what they focus on is white, thin shirtless men partying.

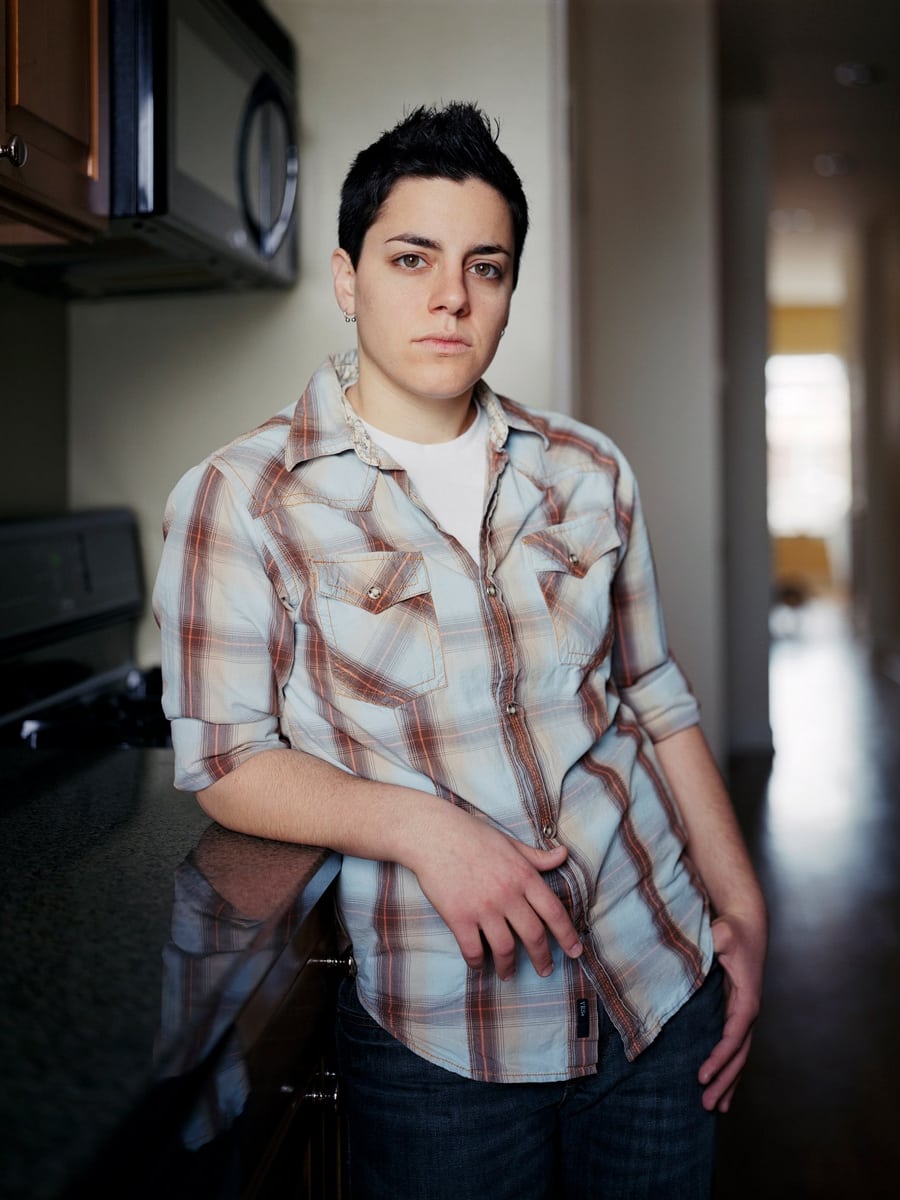

Betsy, 2013. By Jess T. Dugan, from "Every Breath We Drew".

Collin, 2017. By Jess T. Dugan, from "Every Breath We Drew".

The tropes associated with geography definitely trump the tropes of sexuality or gender.

LBR. A few of you already hinted at it, but I wanted to press on it a little more, to make it more explicit: how are the tropes different from one geography to the next?

JTD. To make To Survive on This Shore, I traveled throughout the United States, intentionally going to small towns, to the South, to the Midwest, to the places people don’t think of when they think of trans folks. One thing that really hit home is how different peoples’ experiences were based on where they lived and how hugely different our country is in terms of acceptance, resources, medical care, safe housing, and other issues.

JN. The tropes associated with geography definitely trump the tropes of sexuality or gender. There’s a very clear idea of what a picture of Africa should look like, and likewise in India, and I wanted to challenge those presumptions. When I made my work in Kenya and Uganda, I brought a flash with me. In part because that’s how I approach all of my work. But also because at the time it was an aesthetic that was being used to confer seriousness and also relevance to a given story. I knew I wanted my project to look visually distinct from the work that had been done in the region so far and I felt that it was an aesthetic treatment that stories about LGBTQ+ people from that region also deserved.

DV. We’ve said it over and over, but a huge problem with the media is that we’re competing for the worst story. In Latin America, many countries have progressed in some ways regarding LGBTQ+ rights, even though society has yet to catch up, so the situation with respect to legal protections isn’t as dire as the countries that are further behind, such as in East Africa where LGBTQ+ people can be sentenced to prison terms or even death. The latter is what consistently makes it into the news whereas issues in Latin America get less attention.

LM. Working from South Africa, one of the important to focus on, I feel, is family. Globally, there’s this pervasive idea that LGBTQ+ people are always alone, and discarded, which can be very discouraging for people who are trying to find a sense of community.

Photo by Lauren Mulligan

There’s such a difference between someone feeling empathy towards another, and feeling sympathy, which really is more like pity. You feel empathy when you feel connected to someone. The stories that can help us connect are not those in the extremes, they’re those in the middle, about the everyday.

LBR. Speaking of which, how do the tropes in turn affect the LGBTQ+ community?

DV. People tend to latch onto the tropes and see them as the only truth. For example, if you’re only shown trans people as sex workers, that’s all society will associate them with. Showing a more diverse view of a community will lead to the audience understanding that community better.

AT. There’s such a difference between someone feeling empathy towards another, and feeling sympathy, which really is more like pity. You feel empathy when you feel connected to someone. The stories that can help us connect are not those in the extremes, they’re those in the middle, about the everyday.

And, when you’re someone who belongs to the LGBTQ+ community, we we all need to see ourselves reflected to understand ourselves. I get emails from people saying that reading the stories I worked on helped them feel ok about themselves because they saw themselves reflected.

JTD. For me, it’s about complicating the narrative and showing a wide range of people. On the one hand, I think it’s good for people to have a celebrity or two to point to, but it’s even more powerful to show a range of real-lived experiences and that all of them are different, valid and important. I also want to second what Annie was saying about how important it is to see oneself represented. As a young queer person, there were not a lot of images of people who looked like me in the mainstream. I found Catherine Opie’s work hugely influential and validating.

One of the reasons I wanted to start photographing older trans folks was that I heard from a young trans man who had found one of my images of an older man whom he assumed was trans, but he wasn’t, which in some ways is irrelevant to the story. He wrote this very moving paragraph about how he had never seen an older trans man and had no road map for what he would look like as he got older. So much of the media focuses on people who are murdered, or offers images that are overly fetishized and sexualized. I wanted to create representations that were much more complicated than that for education outside of the trans community as well as for reflection and validation within the trans community.

Finally, I also think a lot about the idea of visibility and invisibility. In this project it was very critical to me that people were willing to share their actual name, their location, and their identity. That, of course, meant that some people couldn’t participate as easily as others. Jake, I wondered, how did you deal with this in your work in Africa?

Nader (left) proposes to Mr. Gay Syria contestant Omar at Omar's birthday party in Istanbul, Turkey. Omar hopes to marry when he is resettled to Norway, where Nader is currently awaiting him. Photo by Bradley Secker from the series "Mr. Gay Syria".

Arkan (20) from Sanandaj, Iran. Chatting on Skype with his girlfriend from Kayseri, Central Turkey. Identifying as transgender, Arkan says: "life in Iran was impossible for too many reasons." After extensive waiting in Turkey, Arkan was resettled to Texas, USA where is Iranian girlfriend also lives. Homosexuality is criminalised in Iran although being transgender is permitted, and the Iranian government provides loans to those undergoing gender corrective surgery. The social stigma of being Trans in Iran drives many to flee. Photo by Bradley Secker from the series "Kütmann".

Ali Reza (28) and Pedram (19) from Terhan and Shiraz, Iran. Living together in a house well known amongst the Iranian LGBT community, Ali and Pedram place a plastic sheet over their garden so they can sit in the rain. Both men left Iran, and came to Turkey to claim asylum for reasons connected with their sexuality. Photo by Bradley Secker from the series "Kütmann".

It was a challenge to imagine how to make work that depicted their qualities such as gentleness, resilience or outspokenness. There’s a certain degree of erasure that happens, even though it’s consensual.

JN. Because the people I photographed in Uganda and Kenya were under very intense danger of abuse and often suffered violence in the past, it was important that their identity be hidden. It was a challenge to imagine how to make work that depicted their qualities such as gentleness, resilience or outspokenness. There’s a certain degree of erasure that happens, even though it’s consensual.

BS. I’ve had a similar experience with people wanting to have their story told and their photo taken, while having their identity concealed. Working on Kütmann I found it difficult to represent those stories accurately and with nuance without being visually repetitive.

AT. When I see that someone can’t show their identity, this makes me very empathetic. I think: “so what, I got beat up when I was 18, I didn’t have to worry about me or my family being killed.” But, I don’t know that it makes my conservative family feel the same.

Bradley’s article made me remember that when I lived in Asia, and in the Middle East, no one knew my ex was a woman and that I had two daughters. I would tell people that I had a husband. Since I had to pretend, lie all the time, these weren’t places where I could have stayed for a long time. In other words, these types of situations prevent the emergence of more queer journalists to cover queer stories in countries where it is not safe.

BS. There’s a difficult balance between coming out publicly and in your private life. At one point Jake, you wrote an article on this subject matter and I didn’t want my name to be used. I had anxiety at that point because I was scared by ISIS. My housemate had received threats from militant groups. My recent piece posted on Medium “You Have to Be a Good ShapeShifter” was essentially the first place when I said it so publicly. You want to be visible but you’re also wondering how it’ll be received by others. Will they think I’m no longer fit to go report in conflict zones?

AT. The more diverse artists, reporters and editors we have, the more diverse stories we’ll get about all things

LM. And, we need this because if the images are always the same, it also means that the narrative doesn’t evolve, which in turn means that we remain in an oppressive state.

DV. In short, a lot of the issues that we’re bringing up here have to do with the lack of diversity in the media in general. Basically, the industry needs a big overhaul.

AT. Amen.

Danielle Villasana is an independent photojournalist based in Istanbul. Her documentary work focuses on human rights, women, identity, displacement, and health. A member of The Everyday Project’s Community Team, she writes frequently for Re-Picture and helped build The Native and Everyday Projects mentorship program, which aims to uplift emerging photographers from underrepresented regions worldwide.

Jess T. Dugan is an artist whose work explores issues of identity, gender, sexuality, and community. Her work is regularly exhibited internationally and is in the permanent collection of several major museums. She is represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, IL.

Jake Naughton is a photographer making work about queer identity in the present moment, ranging from reportage about LGBTQ people in extremis around the world, to intimate images exploring his relationship with his partner. A frequent contributor to The New York Times, his projects have been recognized by PDN, the Magenta Foundation (Project Grant Winner 2016), the New York Foundation for the Arts and others.

Bradley Secker’s work often deals with the consequences of social policies, political decisions, and military actions on individuals. He regularly cover stories about how identity shapes lives in challenging and unexpected ways, particularly within sexual and ethnic minority groups. His ongoing long-term project Kütmaan tells the stories of LGBT asylum seekers and refugees from the Middle East, forced to flee for reasons connected with their sexuality and/or gender identity.

Annie Tritt grew up in NY and got her start in photo though photojournalism there, after several other careers. Photo took her to Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Europe and Mexico. Her current ongoing project “Transendingself” focuses on transgender and gender expansive youth ages 2-20 around the world.

Lauren Mulligan is a photographic artist working in photography, filmmaking and illustration. Her passion is contributing to representations around queer narratives and marginalised racial identities. In 2017, Mulligan was named one of South Africa’s 20 emerging black womxn photographers and completed a Master’s in Film & Television at Wits University in 2018.

Laurence Butet-Roch, a member of the Boreal Collective and Muse Projects, is a freelance writer, photo editor, photographer and educator based in Toronto, Canada committed to encouraging critical visual thinking. Her words have appeared in the British Journal of Photography, The New York Times Lens Blog, TIME Lightbox, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Polka Magazine, PhotoLife, BlackFlash and Point of View. She is the editor of Flash Forward Flash Back.

The conversation continues!

In my work, I try to take portraits of people who sit at the intersection of many different identities, and I especially try to highlight those part of marginalized communities within the broader African experience and diaspora. By doing so, I take a particular interest in those who are both African and part of the LGBTQ+ community and see how they negotiate this intersection, these two worlds that can sometimes conflict with one another. By doing so, but also by looking at what already exists in the media, I realized that many stories of LGBTQ+ folks tend to surround the notion of exclusion, sadness and everything else that can be considered negative. While I believe that it is important to shine a light on the things LGBTQ+ folks go through, I believe that also showing them in a positive light can have a very positive impact on the way the rest of the world see and think about them and therefore how they are going to be treated on a daily basis. Through my work, I try to show LGBTQ+ folks and tell their stories without necessarily centering their queerness but moreso telling these stories in a regular way.

I think geography being a factor in these tropes being different from one place to the next is because of cultural differences. Queerness means different things to different people depending on where you find yourself in the world, because queerness has historically meant different things in different places. A very easy example is the relationship between queerness and the media in Western countries compared to the Global South. In many countries in Africa for instance, conversations surrounding the LGBTQ+ community are largely taboo and forbidden (and in many case, this aversion to queerness is enforced legally) so people would generally have a more negative or at least uninformed opinion about these communities, simply because they are not exposed to them in any real and accurate way.

Yannis Davy Guibinga a 22 years old photographer and visual artist originally from Libreville, Gabon based in Montréal, Canada exploring the diversity of cultures and identities on the African continent and its diaspora.

It’s hard to discuss the visual tropes of LGBTQ2+ visual culture without also discussing how race, gender, age, and class differentially situate LGBTQ2+ people in the visual field. In settler-colonial places like Canada or the U.S., there can be a tendency within mainstream (including queer) media to see “LGBTQ” as a synonym for whiteness, especially cis, gay, whiteness. Efforts to disrupt this equation can sometimes have the unintended effect of exoticizing the suffering of racialized and gender non-conforming people. A focus on everyday lives, can quietly refuse a normative expectation of trauma and its visual performance.

Queer and trans people have always turned to each other, and even sometimes to their own families of origin, to create queer and trans kinship networks. And so many of us document these queer and trans families of choice through the most ‘everyday’ visual genre: the family photograph. We have a tendency to discount the family photograph because of the violence it can do in the context of queer and trans families of origin–the expectation that we conform to norms of sexuality and gender. And while it is certainly true that family photographs can function this way, they can also function to document and materialize queer affective kinships as well, as Danielle has explored in her ‘Simply Family’ project.

I feel fortunate that, in my current work, I’ve been supported by research funding and do not have the same pressure to make work that conforms to mainstream journalism’s expectations concerning LGBTQ2+ representation. The main project I’ve been involved with over the past few years is conducting oral histories with LGBTQ2+ people about their family photographs, and collecting those photographs as part of the The Family Camera Network, a multi-year research project for which my friend and collaborator Thy Phu is the principal investigator. We’ve explicitly focused on transnational migration in an effort to disrupt the whiteness of much of Canada’s LGBTQ2+ history. Our co-curated exhibition Queering Family Photography explores the critical work that queer, trans, and Two-Spirited family photos do in documenting and creating queer modes of belonging–how the emotional attachments of queer family photographs have also sustained LGBTQ2+ lives. In my collaborations with queer and trans narrators of color, I’ve interviewed across positionalities within the overall “LGBTQ2+” umbrella.

Quite a number of them have donated their photographs to the project, and are in the show and in the video we made from the oral histories. We’ve made an explicit choice not to fetishize their embodied histories through label text, for example. As a result there are several trans family photographs where a viewer might well say ‘I don’t know they’re trans’. And my view is: fine. The point of the show is the role of photography in both documenting and creating everyday, quotidien moments of connection and belonging as the raw material for making queer and trans kinship networks; the point is not to taxonomize LGBTQ2+ people and invite spectators to hunt, visually, for the trans subject/object.

Some of the people who we’ve interviewed for the Queering Family Photography show came to Canada as refugees, after having been outed in places like (for example) the Ivory Coast. One of the challenges of the show, and the project overall, is to draw attention to these histories and their photographic manifestations while, at the same time, resisting the tendency of Canadian multiculturalism to use these stories as raw material in building a problematic narrative of Canada as utopian space, free from racism, transphobia, and homophobia.

Elspeth H. Brown is a scholar of photography and a historian of modern queer and trans history and the history of US capitalism at the University of Toronto. She is co-investigator for the Family Camera Network collaborative research project, where her research focuses on queer and trans family photography and oral history, in the context of global migration. She also directs the LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory, a five-year digital history and oral history research collaboration. She is the author of Work! A Queer History of Modeling (forthcoming, Duke) and The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture, 1884-1929 (2005, Johns Hopkins) and has co-edited three volumes: Queering Photography, a special issue of Photography and Culture (2015); Feeling Photography (Duke University Press, 2014); and Cultures of Commerce: Representation and American Business Culture, 1877-1960 (Palgrave, 2006).

When I was researching this a few years back I was struck at how prevalent portraiture is as the predominant form of study. This brings up all sorts of issues about identity politics that somehow traps discussion in a 1970’s paradigm, which is understandable because so many of us still look to that Stonewall watershed as defining how we sit in society.

And, in some ways, it is disappointing that we still use the body as the primary expression of identity because it reinforces the continuing social fixation on sex as the key element in defining sexuality. I’ve often wondered how it would be if we represented sexuality as a continuum rather than isolating LGBTQ identity, which in effect bows to the heteronormative view of LGBTQ as “different”. How would it look if queer photographers interrogated heterosexuality? Would we represent it by costuming people in specific roles?

I suppose much of it is rooted in the conventions of 20th Century documentary that reduces subjects to single-issue beings. At the time of Tim Hetherington’s death he was getting deep into male sexuality as the driver behind conflict and we had started discussing queer representations of the male body, asking how it might be different from straight representations and what was to be learned from the differences. Damn! I miss him still.

And, PS. I am absolutely not an assimilationist! I value my own differences with mainstream culture and my life is enriched by every different experience that others choose to share with me, but I feel cramped by reductive analysis that recognizes any of us only for being different.

Stephen Mayes is Executive Director of the Tim Hetherington Trust. For over 25 years, he has managed the work and careers of top-level photographers at VII, Network Photographers, EyeStorm, and Art+Commerce, amongst others. He also served as Secretary to the World Press Photo from 2004 to 2012. He’s profoundly committed to reflecting and writing about the ethics and practice of photography.

If you’d like to add your voice, submit your response to our editor,

Laurence Butet-Roch at laurence@magentafoundation.org

The Magenta Foundation gratefully acknowledges the nurturing support of Presenting Sponsor TD Bank Group for its ongoing commitment to Flash Forward, in all of its formats, since launching in 2004.

Last year TD has proudly supported 63 Pride festivals and over 100 LGBT organizations and initiatives, including anti-bullying and anti-discrimination campaigns. Learn more »