Urban Legend

Published September 13, 2018

Words by , Laurence Butet-Roch for the Magenta Foundation

Photos by Lawrence Sumulong, 2018 Flash Forward Runner-up

In his series "Urban Legend", Lawrence Sumulong is not chasing the supernatural, but rather evoking the past of the Manila Film Centre, an imposing brutalist building in the Philippines' capital, and by the same token expounding the country's history.

While he nearly made the top hundred list for this year’s Flash Forward Award –he was ranked 101– his images and enthusiastic personality spoke to Magenta Foundation Founder and President, MaryAnn Camilleri. And, it appears, she’s not alone. The series is part of the Imagined Nations/Modern Utopias exhibition which Clara Kim, senior curator International Art at the Tate Modern, put together for the 12th Gwanju biennale.

Kim’s intention in organizing the collective show was to “create a provocation about the fate of architecture and its changing meaning over time. The effects, afterlives and conflicted legacies of these projects become provocative framework for understanding the formation of modern identities. In a contemporary context where the make-up of nation-states is being contested today, it is important to look back at these histories —and the architectural monuments we have inherited, and be reminded of the important role that imagination played in the construction of a shared or collective identity.”

The main theater of the Manila Film Center.

Jason Moon, the owner of a Korean restaurant that operated inside the Manila Film Center, looks out towards Manila Bay from the Manila Film Center.

In this particular context, not only is Sumulong’s work in great company (alongside the likes of Yto Barrada and Damián Ortega), but its layers of meaning can be fully grasped.

A second generation Filipino American, Sumulong visited the homeland in 2012 to better understand the country of his parents and explore his relationship to it. commissioned by curator Patrick Flores of the Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Gerard Lico, a Professor in the University of the Philippines Diliman College of Architecture, he focused on a single building, the Manila Film Center. “What I found inside the crumbling structure was the proscenium of Philippine history, its tragic past, and unscripted future playing itself out. The Manila Film Center’s arc remains the most compelling to me as a reflection of post-EDSA [the People Power Revolution in 1986 that led to the end of the Marcos dictatorship],” he says.

The stage of the main theater inside the Manila Film Center.

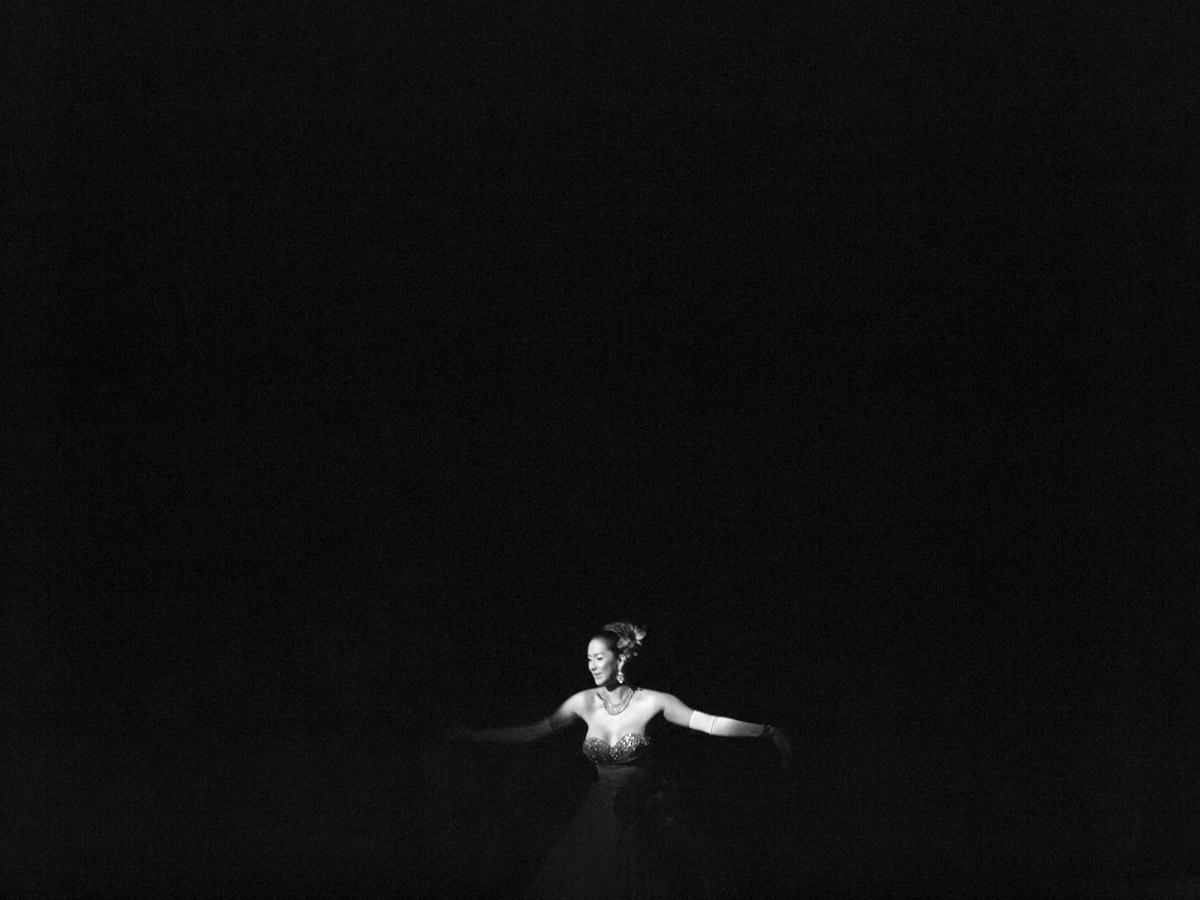

A transgender performer at the Amazing Show lip syncs the song "One Night Only" from the film 'Dreamgirls 'on the main theater of the Manila Film Center.

Built in the early 80s, while the nation was under martial law, its creation and development was spearheaded by Imelda Marcos, then first lady. It was to house an official film archive; as well as viewing rooms for the Board of Censors. A state-propaganda machine, it also became a symbol of the ruthlessness of the regime. Eager to complete the project, the government imposed exacting work conditions. When scaffolding collapsed, at least 169 workers were killed. They were immediately buried under quick-drying wet cement, some allegedly still alive, without rescuers being allowed on-site until 9 hours later. The ghosts of the dead are said to haunt the premises.

Abandoned after the 1990 earthquake, it became cruising grounds for members of the LGBTQ+ community before being rehabilitated and then leased to the Amazing Philippines Theater, a Korean company that produces the Amazing Show, which features only transgender performers. In 2013, a substantial fire razed a portion of the structure. Much of what Sumulong photographed was entirely destroyed or is now inaccessible to the public.

“I think society is quick to write off its story as a type of sideshow. It’s easy to say that this trajectory represents a type of Icarian ascent and tragic fall into disgrace, but that speaks nothing about the character of its creators or the reality existing inside the MFC. To nostalgically interpret the MFC’s fate simply valorizes the ideals of its corrupt dictators,” believes Sumulong who would rather focus on teasing out some of the ironies at play. Intended to be “a monolith for international cinema” by a regime that upheld heteronormative ideals by positioning themselves as the first family of the Philippines and the model to strive for, it became the playground of marginalized communities.

Casie Villarosa, head of operations at the Amazing Show, and Jason Moon, the owner of a Korean restaurant that operated inside the Manila Film Center, sit inside Villarosa's office on the 2nd floor.

Casie Villarosa and Jason Moon use the firing range built in the basement. The space is often used to train local Manila policemen to practice with and responsibly handle firearms.

Backstage in the main theater of the Manila Film Center.

Casie Villarosa records an audition for a new segment in the show inside his office on the 2nd floor of the Manila Film Center.

Sumulong’s images, while all made in 2012, speak subtly of both past and present. Amidst images of the performers roaming backstage, there are glimpses of nationalist frescoes, commemorative graffitis, discarded film archives, and even a basement shooting range. Informed of the history of the space, we confer additional meaning to each frame.Silhouettes become ghosts, the brutalist architecture stands in for the Marcos dictatorship, rifles hung on an office wall hint at enduring violence. As Kim’s suggest in her exhibition statement, photographs of “architectural monuments” can reveal as much about the construction’s life as it does about a nation’s ongoing metamorphoses.

“One image in particular that resonated with me was the engagement photo shoot on the roof of the MFC. It was between Jason, the restaurant owner of the Korean restaurant at the MFC and Mishel, a Filipina. I actually attended their wedding, which juxtaposed two very different cultures. There was something beautiful about their story and the way in which they were both moving beyond expected social and cultural mores to join together in marriage,” he remembers “In an increasingly brutal and severe Philippines where citizens are being killed for prejudicial reasons, I’d like to remember that moment of unity and understanding.”

See more of Sumulong’s work on Instagram @magentafoundation