Cover photo of Laurie Metcalf, Glenda Jackson, and Alison Pill by Mackenzie Stroh

HM. While I can’t remember how I came across Alreadymade, I’m deeply interested in it, not only because of its role in creating diversity by spreading the word around great female talent, but also because it brings up this question of whether there’s a distinctly female perspective and its place within the editorial and commercial industry. Jill and Mackenzie, can you talk a little bit about the impetus behind the directory?

JG. It’s a little tricky because when you’re doing an advertising job, you’re executing a pretty specific brief. A lot of times the photographer has the least amount of power to make decisions. But, at the same time, the dynamic of the shoot is always captured in the photograph and even more so in an editorial context when we have much more impact and control on the way things look. Power, sexuality, etc., everything is there. So, if it’s all men making these images that are marketed primarily to women, there’s something wrong.

But as we know, it's not a meritocracy. The political and societal rules around who gets jobs in any industry leave women out.

The images that we see are always filtered through the eyes of the person taking the photo. Hence, it’s a major issue that no one was talking about the fact that all these women were seen through a man’s eyes and a man’s brain; that the reflection was always through the eyes of a male figure. Building on that, if women are good enough, women should be getting those jobs too. But as we know, it’s not a meritocracy. The political and societal rules around who gets jobs in any industry leave women out. That’s the most basic aspect of Alreadymade.

JM. In my experience so far, especially in the last five years when I was at Droga5, there was a big push for using diverse talent in terms of artists that came from the agency, but also from brands as well. Take Under Armour; in the last few years, they’ve had a strong presence of female athletes, like Misty Copeland and Lindsey Vonn. They would actually ask us to make sure there were women photographers on the list we send them. You could start to see a bit of difference between women’s work and men’s work, especially with sports. But sometimes you can’t and that’s really interesting too. The last campaign I did with a woman was Cass Bird and that was really great too because we were shooting their [Under Armour] Sports Bra line. We were looking for intimacy, truth and bareness with these female athletes, and so in my opinion, it was perfect to cast a women to shoot that.

MS. One of the times I realized I not only had a unique perspective but also a duty as a female photographer to portray women in certain ways, I was in Montreal and I was shooting for Saturday Night magazine. They were doing a spoof of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue and I was commissioned to photograph several Canadian celebrities– one of them a successful female WWE wrestler. We set up a backdrop and small set at the wrestling arena, behind the scenes. I had a female assistant and within the first little while, the main photographer for WWE comes in and starts grilling me on my technical choices (lighting ratios, lens choices, etc. I knew he would never question a male photographer like that. We finished the shoot – and we all had a great time and got some beautiful, fun, respectful photos. But then the main photographer says to me: “Let me show you how I would have shot this.” And, I’m not exaggerating, he backlit her, put in these overtly sexy poses, and started snapping his fingers at her like a dog. I had my jaw on the floor, my assistant had her jaw on the floor and I thought: “No. Never in my life would I photograph someone like that.” It was a wake-up call.

Nowadays, I know that sometimes I’m only getting a job because they want a woman. While there’s a power in that, it should be an equal playing field, we should also be hired to shoot men. I think that’s the next step.

Nowadays, I know that sometimes I’m only getting a job because they want a woman. While there’s a power in that, it should be an equal playing field, we should also be hired to shoot men. I think that’s the next step.

HM. Thank you for giving that example. I’m curious to hear from Michelle about the reasoning behind forming Sofia.

MY. We started Sofia in 2014. Even though it was not that long ago, a lot has changed in the landscape since then in terms of the women’s movement. We weren’t coming together because we thought we wanted to forward the women’s movement, we were craving community. In Toronto, I just found that my male friends who were in photography would go out for drinks regularly. Their social time for networking and talking about ideas with each other was already incorporated in their lifestyle and within my own network of women photographers, we didn’t make it a priority unless it was about work somehow. It could be because we had different priorities or different ways of socializing but we created Sofia because we wanted community.

I think that as women in the industry we have that tacit understanding of what it means to be a woman in this world, what it means to be a woman in this industry. So while it wasn’t an explicit part of our mission at the time, after we became public with our first exhibition I realized how much there was a need to have that community and sense of security and safety where we could talk about the challenges we were facing as professionals and how we could address them. Now, our focus is more on mentoring women in photography. One of the thing that shocked me with the #MeToo movement was to hear how men with power in the industry were using mentorship as a way to victimize young women.

Sofia "Bad Behaviour" exhibition opening

HM. Both Alreadymade and Sofia defend the place of the female perspective in commercial work Kristina, as someone who’s just starting in this industry, what do you make of Mackenzie’s horror story.

KD. A lot of times, you are treated very differently as a woman assisting on set, especially by men. I’ve worked with photographers who say, “you’re the only female assistant I’ve ever worked with,” which is shocking because in photo school it was mainly women in the program, and then you don’t really see them around afterwards. I’m wondering what the disconnect is there: why are male photographers not hiring female assistants. In Toronto, there’s a roster of female assistants which I think is great but I hope photographers see this list and then actually use it.

You want to be included for your merit and point of view, not just to be a placeholder in someone’s paperwork.

JG. It can be hard to see the sexism because it’s not often as blatant as Mackenzie’s story. One time I was giving a talk and someone asked: “what’s it like to be a female photographer?” I answered: “I have no idea what to compare it to because I’m not in those conversations.” In other words, you rarely hear what people say behind closed doors and sometimes your agents don’t really tell you things like they are. But some agents have told me that when they represent a woman vs. a man, they only make half as much money.

F Collective wants to do something sort of like Free The Bid, where people agree to include a woman in each bid. I’m always in triple bids and I’m the only woman. Still, I’m not getting the job. I’ve heard an art buyer say they feel like its a risk to pick me because I’m a woman. So, I don’t think including a woman in every bid is the answer. After all those take a lot of work to put together. Do I really want to have ten more bids to prep a month that I’ll end up not getting? Not really. When you get a job, it’s because they want you. Period. There’s always a choice, there’s always someone who they really want, so throwing another person into the bid isn’t going to help you get the job, it’s just giving you additional unpaid work. What do you guys think about that?

JM. I agree. You want to be included for your merit and point of view, not just to be a placeholder in someone’s paperwork.

Photos by Jill Greenberg

SS. I’d like to chime in, not to disagree but to add a little more to it. The way I see it, I’m also dealing with creatives or team members who, because of a sense of familiarity think, “oh, put up our usual three.” Though bids are a lot of work, they are also opportunities to learn and be introduced to new people. It could be a first step to open the eyes of the people who might be entrenched with what they’re familiar with.

But to be asked to get a token bid, that’s when you push back against your people and say: “this isn’t right.” Within the agency world, we’ll fight that fight.

That’s the problem in this industry. If we keep hiring the usual suspects, then we can’t prove our ability. If we don’t get that opportunity, there’s no moving forward.

JG. On Already Made, I’ve written, “please consider hiring women for 30% of the jobs, instead of 10%”. I don’t know what else to say because I’m not suggesting the token bid.

MS. It has to start at a very base level: assisting or being mentored. That’s where you gain so much knowledge. When I look at the male assistants I’ve worked with over the years, they are so savvy now because they’ve been on so many sets. There’s so much information coming at them every day and then they move up the ladder, meet all these art directors and photo editors and build relationships. If we don’t get more female assistants (and not just studio managers) that are actually working the equipment and showing that they have that technical knowledge, then they can’t move up the chain.

I had a new client last year. The talent was quite difficult and some things on set were challenging, but I showed that I could handle any type of person and from there they hired me again. If we don’t get our foot in the door, there’s no way to prove what we can do. That’s the problem in this industry. If we keep hiring the usual suspects, then we can’t prove our ability. If we don’t get that opportunity, there’s no moving forward.

Saoirse Ronan photographed by Mackenzie Stroh

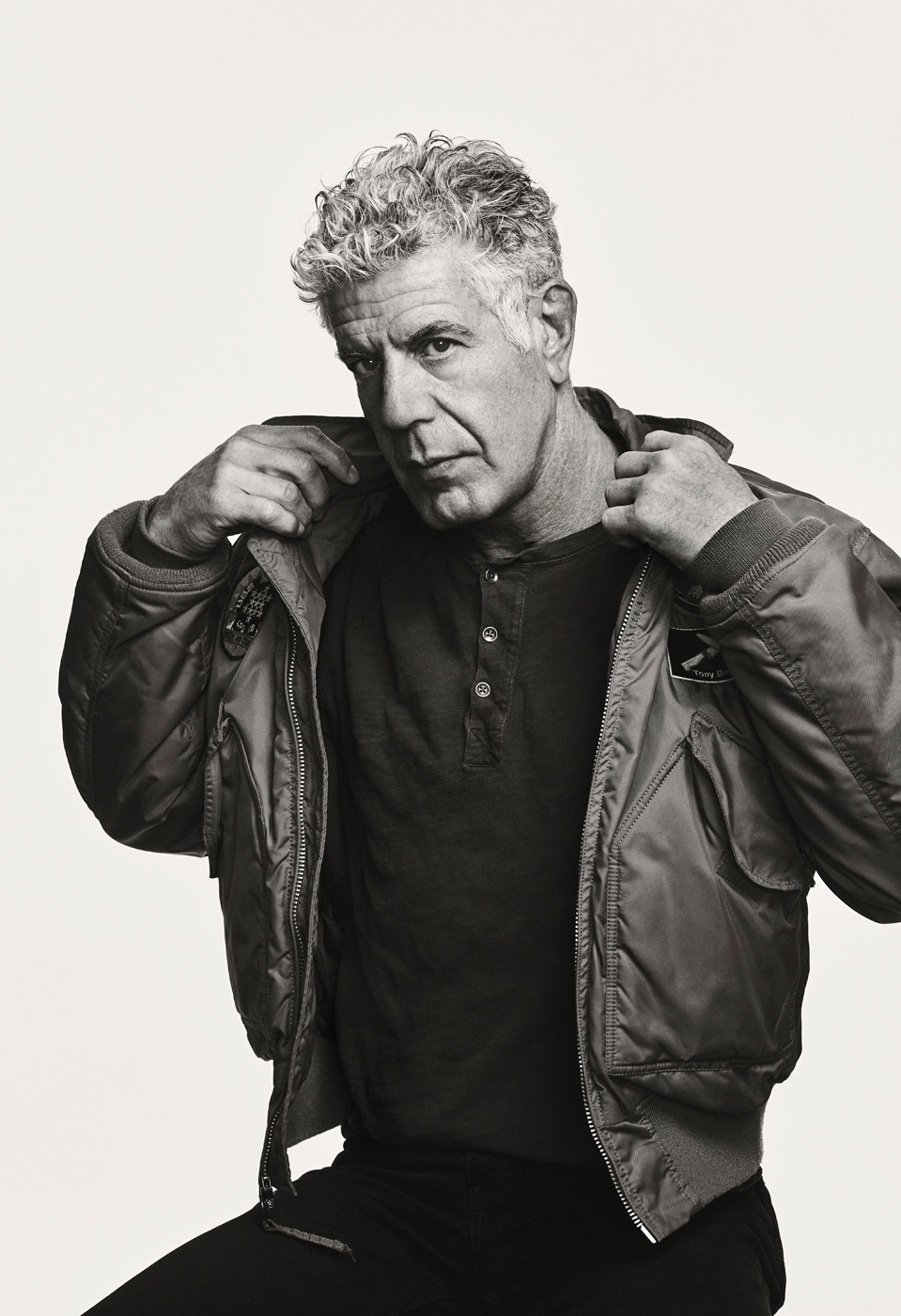

Anthony Bourdain photographed by Mackenzie Stroh

HM. It goes to what Michelle was talking about Sofia’s direction and the importance of mentoring; so that women coming out of school can see that there is a future in shooting. When I came out of school, I was really good at assisting and producing. I find that women get a lot of praise around those abilities and those jobs are easier to get so we see a real attrition by young women who are pursuing commercial shooting but tend to leave to take producerly roles.

JM. On the agency side, there is a lot of trust on the part of male coworkers when you’re in the producer role because you take care of everyone. There’s a lot of “mothering” going on. I’ve felt that often on the jobs I’ve done.

In the last few years at Droga, I have pushed whenever I have photographer meetings to get women in the agency to come. The face-to-face is really important, especially if you want to be considered for a job down the road. If the creative teams can actually see your work in person and talk about other things besides the industry too, that helps a lot.

It’s all about relationships. One things that sounds really cold to say now, is that there are so many people that shoot the same thing. When all the promo-emails and cards you receive are the same, how do you pick one person over the other? Personality. I’m actually doing a lifestyle search now and I’m thinking about personalities; here is the creative team I’m going to be working with, it could be a 3 to 5 days shoot. It could be somewhere like LA, so you’re going to be travelling with people, basically living with them. I know all of these people can shoot this well so who do I think is going to get along?

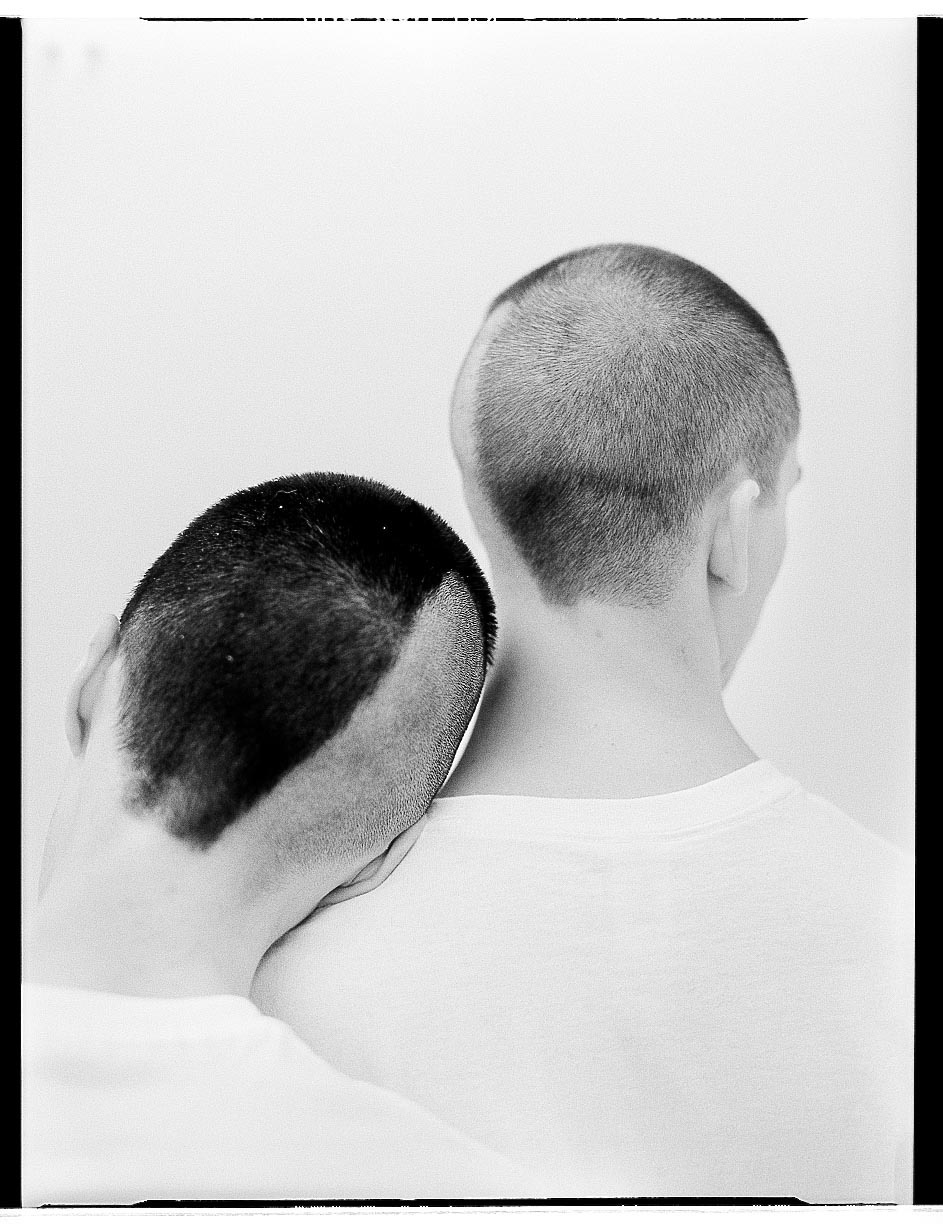

Photo by Kristina Dittmar

HM. Gender plays into all of that too, especially that picture you’re painting about travelling, and that intimacy you have on those jobs. I don’t know if any of you have anything to add in terms of that? Have you felt like your gender is part of that puzzle? For better or worse? Like you’re not getting those jobs because of that intimacy? Or there’s a perception that you’re just not going to fit?

MS. I was obsessed with my career for a long time and then I had my son and I had to stop travelling for a while. In one of the first calls I got after he was born, I was asked if I could fly to Arkansas and I knew I couldn’t with a newborn at home. The editor was kind of disgruntled and I realized how hard it might be for a woman in this business, where a fair amount of jobs are last-minute and require a lot of flexibility. Another photo editor told me that she didn’t call me because she knew I had a young child. Ideally, it would be my decision, to take a job or not based on my life situation. So that’s a disadvantage that I don’t think a lot of male photographers have to think about in the same way.

JG. Then there’s also the ageist thing. People are not hiring me because they think I’m over the hill or something. And with increasing demands for behind the scenes footage, there are expectations of what the photographer looks like in that content, and an older woman might not fit that bill.

HM. Are there more demands for women about how they present themselves to potential clients?

JG. When you’re a woman in the world you have to care what you look like.

Photos by Jill Greenberg

HM. Even around being forceful. Do you feel like there’s an expectation that you defer to a man a little more?

MS. In this field, often you have to make sure that the work reflects your vision and is done your way. That means kind of being “bossy”. That’s not a term I like to use for women, but you have to take charge. You set the tone and you tell people how to do things. This is the role of a good photographer. You’re the one getting blamed if those images are not good, you’re the one getting praised if they are good. So the crew you hire the people you surround yourself with, it totally matters.

That said, there is also beauty to getting older in this business. It’s like, “I don’t care if you like my photos anymore, I like what I’m doing.” I’m getting more work because of that. Maybe less work too.

Probably a bit of both. I’ve stopped pleasing people as much as I used to.

JM. It’s really important to show that you have control over your set and I think that results in more respect from the creatives. Keeping that confidence and that control is something I definitely look for, whether you’re male or female, but as a woman, you have to be a lot more careful because I think you’re more scrutinized.

Photos by Kristina Dittmar

KD. Have you ever been challenged on set?

MS. For sure. Male assistants, especially ones that are very experienced might say “it’ll look better like this” and I have to say, “no, I like it like this”. And I do appreciate good assistants that actually see technically better than I do but you also say, it’s not just about the technique, it’s about the experience and my ability to connect with people is what makes me a good portrait photographer, so step back and let me do my thing. But being challenged by men? All the time. I’ve had people think that I’m the hair and makeup or the producer and I have to say, “No, I’m the photographer.”

What are the different ways I can model, how can we create a meritocracy? How can we make women be totally equal players, without having to rely on tokenism?

MY. I keep thinking about us having this mentorship program and how to prepare women for these things. I actually didn’t think about power dynamics on set until I was interning for a male photographer and he sort of pulled me aside and said stuff like: “Did you see what that other assistant was trying to do?” He went on to explain to me that he had to show him some push back, that he was controlling the set.

Maybe it’s because prior to that, every set that I had been on, I really trusted the people I was working with and so I was much more open to collaboration that I was only focussed on that; I was naïve in imagining that sets were devoid of such power struggles. It would have been so great to assist more women photographers to see how they handle it. When you’re in a situation where there’s a lot of people working, there are a lot of stakes and relationships there, there’s not really a rulebook for how to conduct yourself or how you can be an easy person to work with, but still control a set. In terms of filling this gap, and how to better prepare women in this industry, that conversation is so valuable; “What are the different ways I can model, how can we create a meritocracy? How can we make women be totally equal players, without having to rely on tokenism?”

Photo by Michelle Yee

JG. I remember before I photographed Martha Stewart, people were all saying she was really mean and when I met her, I didn’t think that at all. She was very forthright and she asked a lot of questions about what I was doing. Women behaving in the same way that a man behaves get called “bossy bitches” end of story.

MY. How do we change that perspective? Where a woman who is speaking her mind, and being direct, is not automatically labelled a “bitch”?

JG. When you’re a woman you have less control over that and once you’re branded difficult you might as well just give up, because there’s nothing you can do once you’re branded difficult. It’s frustrating. Sometimes I would hear that a certain photographer refuses to do so and so. And that photographer only gives so many shots, he won’t give you the whole edit and that photographer is kind of a dick. And I ask “And you still work with that photographer?” And the answer I get back is well… “he’s a known thing.”

MS. I feel that’s societal. That there’s a badge of honour for men to somehow be more commanding and demanding than women in any industry. If women have that attitude, it’s seen as somehow being more challenging to work with them, when really it isn’t. That’s not just photography, it’s everything.

Photo by Michelle Yee

HM. While I know you can’t generalize, I would like to query this idea of whether there is something specific you feel like you might be bringing to the table for a client, as a woman?

MY. A lot of posing techniques were designed to make a woman look thinner or shapelier. Maybe question, “what do I think is beautiful in a woman?” I’ve learned and internalized these ideas, “this is how you pose a woman to accentuate or de-emphasize certain qualities and I have to question that for myself. I have to ask, “is that even an aesthetic that I actually want to attach to? Or is that just the default of how I’ve learned women are supposed to look?” I don’t know if men even ask themselves those questions. Especially now that there’s so much more body acceptance and more gender fluidity, I think being a woman, because we’ve been operating at a disadvantage, we have more to offer because we understand what that is. We are much more sensitive to the issues because they affect us on a very personal level.

A lot of posing techniques were designed to make a woman look thinner or shapelier. Maybe question, “what do I think is beautiful in a woman?”

KD. There are a lot of iconic images made by men that instill this idea, of how you pose a woman, but when you’re a woman, you pose them differently. You wouldn’t show them in a vulnerable, seductive way, that traditional male gaze in a sense. That’s not how I want to portray women, that’s not how I want to be portrayed. I think it’s viewing women with more respect, and shooting with a more respectful eye that’s still aesthetically engaging. It doesn’t have to be about sexuality.

MS. A good example is this last shoot I just did. I was photographing these very high powered women in Washington, and the PR people were very obsessed with making them look pretty and friendly. I thought, “why do they have to look so pretty?” and kept saying “Can’t they just look strong?” One of the women, she was very obsessed with her hair and she had great hair, but her expression was kind of vacant, just pretty and I said, “You are a badass in Washington!” It was amazing how her expression changed.

SS. As image makers, no matter what, even if there is a brief or a prescriptive art director, a piece of you is in the work. So some of that perspective will come through. I think there is a value there, especially when we are speaking to women. We have the spending power when it comes to consumption right now. So even that razor ad is speaking to us more. So why not have a woman’s voice come through.

JM. And everyone wants to be doing something different. For me, pushing that you’re going to get something new in a good way, creatives find that exciting. They want to be doing something different, saying something different.

HM. I like that we’ve touched on how it comes down from the decision makers, some of which are in the room, and the issues around assigning, and the boys’ culture that exists in advertising. Ageism is another issue. To this idea of mentorship, it has to come from both ends of the spectrum, both by empowering women as decision-makers and bringing up women as assistants. It’s multipronged in terms of workflow as well. Diversity, it’s important to acknowledge, isn’t just about gender. It’s still a very heteronormative arena and some work has to be done around being more inclusive of people of colour photographers: Diversify Photo and Natives Photograph seem to be good first steps. And, I guess it’s kind of having a moment.

Heather Morton is currently a Professor in the Honours Bachelor of Photography Program at Sheridan College in Oakville, Canada. She has developed and now teaches courses in Photographic Theory, and the History of Advertising Photography at the senior level. Prior to this, she worked for many years in advertising as an Art Producer at several Toronto-based agencies including Leo Burnett, Zulu Alpha Kilo and Cossette. Between 2008 and 2011, she also authored the popular blog HMAb which covered all things related to the commercial photography industry.

Since the age of 10, Jill Greenberg has staged photographs and created characters using the mediums of drawing, painting, sculpture, film and photography. She is known worldwide for her uniquely human animal portraits, which intentionally anthropomorphize her subjects, as well as her infamous series, “End Times” which struck a nerve in its exploration of religious, political, and environmental themes exploiting the raw emotion of toddlers in distress. Her recent work marks a return to the postmodern feminist theory that inspired her senior thesis, “The Female Object” as an art student at RISD in the 80’s.

Julia Menassa‘s start into the advertising world was at Toronto’s Ammirati-Puris, followed by jobs at Cossette Communications-Marketing, TBWA and Droga5, where she collaborated with brands such as Under Armour, Hennessy, and Diet Coke. Along with working with some of the most prominent photographers, she is dedicated t cultivating the careers of promising, young up-and-comers.

Born and raised in Western Canada, Mackenzie Stroh knew she wanted to be a photographer after she first stepped into the darkroom at age 12. She studied Multi-Media at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver and completed her MFA at Concordia University in Montreal. She loves portraiture in its many different forms: playful and energetic to intimate and introspective. Whether photographing an actor, author, politician or someone with a story to tell, she aims to create an atmosphere where subjects feel at ease and authentic images can be made.

Kristina Dittmar is a photographer based out of Toronto. Her work is heavily inspired by the idea of home and the intimacy that occurs when photographing a subject. She is a recent graduate from Sheridan College’s Bachelor of Photography Program.

Michelle Yee is a Canadian artist, photographer and writer, based in San Francisco, California. Michelle will be publishing her photo novella, “After that August” in early summer 2019.

Setareh Sarmadi is the studio Production Lead at Hiku Brands.

The conversation continues!

If you’d like to add your voice, submit your response to our editor,

Laurence Butet-Roch at laurence@magentafoundation.org