LBR. What does it mean to photograph a person, or a community with dignity?

ATL. To treat someone as you would want to yourself or your family to be photographed; that is with respect. I think it’s that simple.

KS. It implies making someone feel safe. And, in my practice, that involves collaboration. I’m careful to use language that conveys the idea that we’re making something together, as opposed to this notion of ‘taking’, especially in the context of Indigenous communities.

EB. Immediately, I think about the act of listening. Before taking the picture, we will have a conversation where I learn about the desires of the people I’ll be photographing. This allows me to capture their story, and what they’re trying to say as a community more accurately.

Melaw Nakeko II. Photo by Kali Spitzer from "Tin Types"

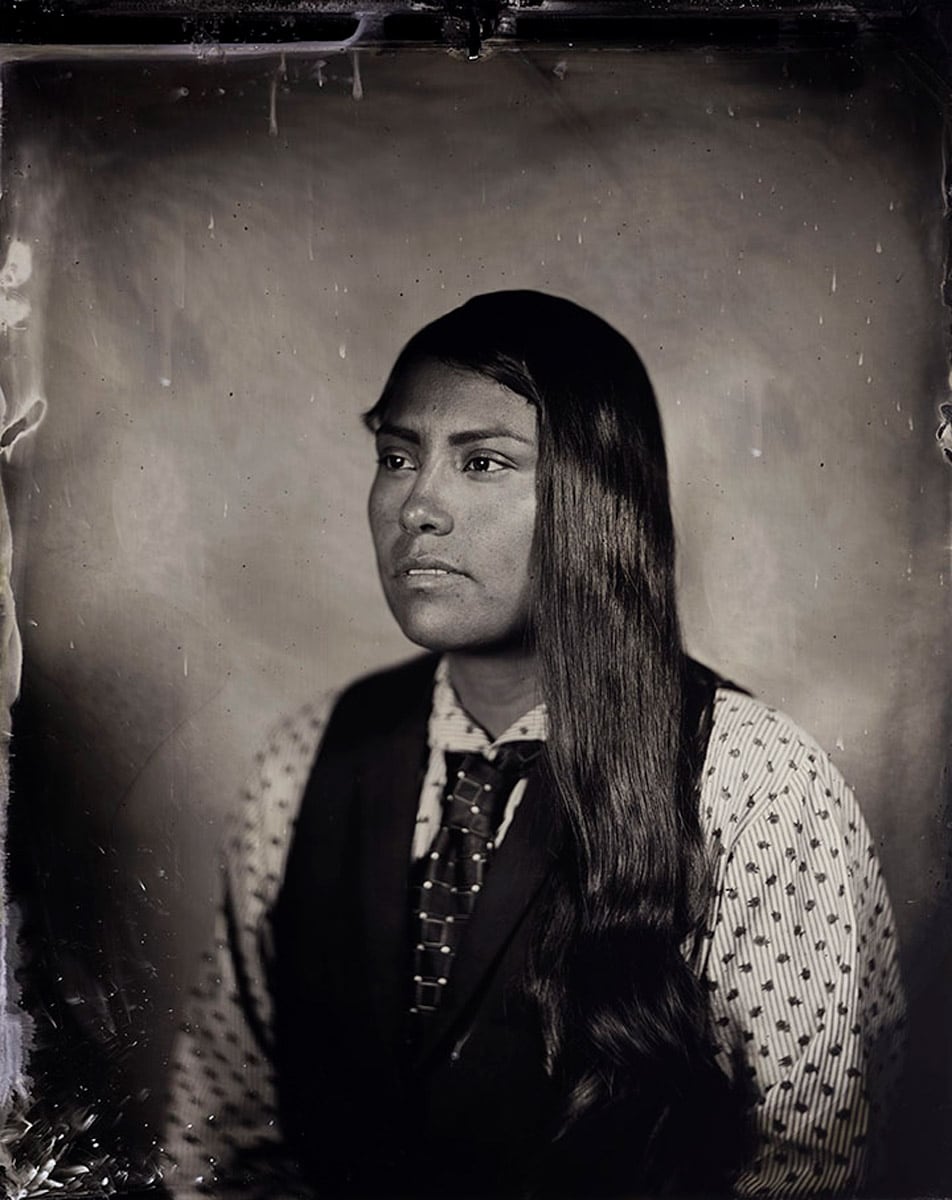

Angel. Photo by Kali Spitzer from "Tin Types"

Dignity is very fraught. For many years, that term has been used, to a large extent amongst documentary photographers as a sort of bourgeois self-appeasement, which helps make one feel better about their work.

SM. Anastasia used a really important word: respect. I find it to be more useful. Dignity is very fraught. For many years, that term has been used, to a large extent amongst documentary photographers as a sort of bourgeois self-appeasement, which helps make one feel better about their work. There’s a huge difference between dignity and respect. On one hand, one can photograph a huge number of undignified situations with respect. On the other hand, seeking the dignity of all subjects leads to all sorts of dangerous territories. For example, what does that mean when photographing politicians? Or someone you’re in opposition to? If one adopts the process of conciliation or collaboration as their model, then one has to apply it across the board.

AB. Dignity calls for representing people so that they come across as fully complex human beings rather than trying to fit them into reductive categories. People can be shown in a very difficult part of their life with dignity if we demonstrate that it is just that: a part of their experience, not their whole identity. Plus, a complex portrayal helps break down barriers between “us” and “them”, “viewer” and “subject”, since most people can relate to having one part of their life together, while other things seem to fall apart.

BD. Dignity is our value as a human being. In photography, it means capturing the subject as a human being, doing it with a lot of respect and intending to give an authentic representation of who they are and where they are at in their life.

Aimee signs her mother's memorial, in the place where her body was found, after visiting it for the first time since it had been discovered there in 2012. Her aunt that she isn't on good terms with has her mom's ashes and, without a grave to visit she feels disconnected from her mom. Photo by Amber Bracken from "7 Generations"

If we intend to document life truthfully and honestly, then it necessarily involves a certain amount of undignified representation.

ATL. What makes it so difficult for us to talk about dignity, is that it is hard to define. It means different things to different people. The solution then lies in having a multitude of different voices, perspectives, and sets of eyes looking at issues and communities.

KS. I like the idea of using the word respect over dignity because it feels more specific: showing cultural respect, having respect for the person in front of the lens, having respect for what you’re doing together. It holds more weight and is easier to comprehend.

AB. I also like this idea of striving for respect because it is about being able to truly see somebody as they are, and respecting that reality. That’s the most fundamental thing we do: we see people; sharing the experience with others comes later. But first we connect with a person. I don’t think you can respect the reality someone is experiencing if you’re hyper-focused on doing a certain type of representation whether positive or negative.

How Anastasia handled her assignment with the Rohingyas is really beautiful in terms of acknowledging what is going on without farming their agony in a gross way. She found a way to tell these stories with integrity, while respecting the reality of what occurred. It would be a disservice to gloss over what they’d been through.

SM. The danger of using dignity as the overriding ethos is that it also involves dishonesty. There is much in life that is not dignified. If we intend to document life truthfully and honestly, then it necessarily involves a certain amount of undignified representation. That’s where respect becomes so important.

LBR. How has your personal understanding of what photographing with respect mean evolved over your career? For instance, Anastasia, we’ve talked about those notions in the past, when an article I wrote for the British Journal of Photography about your work on the Rohingyas was initially posted under a heading that was roughly ‘Photographer Gives Dignity to Refugees’. Readers rightly pointed out that a photographer does not give people dignity, that people have it. Was that a defining moment for you?

ATL. It’s also worth pointing out that neither of us titled the piece and that it was quickly addressed and rectified. Thinking about that specific work, I should first speak candidly and ask: do we really need another white woman from one of the world’s richest countries going to one of the poorest one and photographing brown women who have been raped? I’m pretty certain the answer is no. That said, it was an assignment from Human Rights Watch for which I am very grateful. I was given an unusual amount of freedom. I started by photographing in a very traditional reportage way, showing groups of refugees waiting in paddy fields as they escaped violence in Burma and made it to Bangladesh. As I was doing that, I came to see that I was representing Rohingya women in a different way than I would those from my own community. That realization prompted me to create a makeshift studio and to resort to traditional portrait aesthetics. I felt that was more respectful.

AB. I had an epiphany when I was photographing for a prostate cancer fundraiser very early in my career. The campaign asked photographers to contribute portraits of strength to counter the narrative that prostate cancer was embarrassing and dehumanizing. I ended up being paired with a survivor and made an image where he had a cape on, posing more or less like a superhero. Sure, he looked dignified and powerful, and he liked the picture, but he did tell me that this was not his experience of prostate cancer. I had gone too far in wanting to serve the campaign’s message. I did not initially talk to him about what his experience was, how he felt about prostate cancer, what it was like to have it and survive it. There’s ugliness, and fear, and often undignified moments but I missed all of that.

SM. That’s a very telling story. Dignity is aspirational and might not represent the reality.

Portrait of Donna Simpson, painting her toenails in her bathroom in Old Bridge, New Jersey, United States. At the time of this photograph (in 2011), she weighed 602 pounds and expressed a desire to reach a target of 1,000 Ibs. She holds the Guinness World Records as the "Heaviest woman to give birth”, when she gave birth to Jacqueline in 2007 weighing 532 pounds. Donna maintained a website where fans pay to watch her eat and accessed photos of her body. She called herself a “body entrepreneur.” Some fans sent her food, she also received hate mails. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus from "Globesity"

BD. I’ve learned that trust and building relationships are key. When I photographed Donna Simpson –who holds the World Guinness Record for the “Heaviest woman to give birth”– for a personal project on global obesity– I asked her how she would like to be portrayed. We spoke about tolerance, her experience with emotional abuse and about how she sees her body. I could see some people would say could be exploitative but its not; it was the outcome of an exchange. She’s proud of who she is, what she looks like.

SM. Dignity is contextual. One can behave with dignity, be photographed with dignity, but then when that image is shown in a different environment, the behaviour is interpreted as undignified. So dignity is not a fixed measure, it shifts.

LBR. Speaking of how viewers interpret photographs, Bénédicte, you were recently involved, over social media, in a discussion surrounding a photograph taken in a shelter for elderly sex workers of a woman showering. Some people were wondering whether it was respectful to photograph her in such a situation.

BD. I had the opportunity of doing a takeover of the Women Photograph Instagram account, and thought I would share work from the project: The women of Casa Xochiquetzal. I posted nine images on the feed in total, opening with another portrait of Juanita. However, given the nature of the platform, some people who only saw that one photograph of her, and not the whole, limiting access to the whole context. Many disagreed with how she, a sex worker, was represented showering and questioned my position as a white photographer working with a vulnerable group of people. From there, they unfairly questioned my ethics based on their interpretation of how uncomfortable Juanita felt in front of the camera and assuming that I took that image with only the deliberate intent of furthering my career. I have a deep relationship with Juanita, as well as most of the women, social workers and the director of the shelter. After taking the image in question, I showed it to Juanita and we discussed it. She fully agreed to having it publish in print and on social media platforms. When I told her the comments that it generated online, she said: “you can’t see nothing in that photo. I’m not even nude”, adding that she liked it and wanted a copy of it. I

I think there’s a fine line when thinking about representation and dignity. Our job, as photographers, is to show people’s reality honestly without the subject feeling demeaned or degraded. Juanita wasn’t uncomfortable in front of my camera. The image captures her emotions when she forgot my presence. Personally, I think, that’s really moving and telling.

Sonia, a 62 years old resident of Casa Xochiquetzal, prays at a church in Mexico City. She left home at 11 to escape abuses. During a party, when she was 14, a man raped her, then shot her in the head to keep her quiet. The bullet remains lodged in her head. The attack left her partially paralyzed on her left side, and pregnant. She moved to Casa Xochiquetzal after one of her daughters stole her life savings. June 2012 Photo by Bénédicte Desrus from "The women of Casa Xochiquetzal"

Portrait of Juanita, a resident of Casa Xochiquetzal, in her bedroom at the shelter in Mexico City. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus from "The women of Casa Xochiquetzal"

Elia, a resident of Casa Xochiquetzal, talks to her dolls as a method of coping with her past life, in her bedroom at the shelter in Mexico City. February 2017. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus from "The women of Casa Xochiquetzal"

Dignity, respect, or honour can be exuded through a photograph, but there are limitations to our medium. So, we have to start thinking about other mediums which can assist in filling those gaps.

LBR. As the discussion unfolded online, I wondered how can a photograph show the relationship between the photographer and the photographed, the process through which trust was built, or how those involved collaborated?

BD. Intimacy is an indicator. You wouldn’t be able to get this close to someone if you don’t spend time with them, if they don’t trust you. Still, there’s a lot the public will not know. For instance, with this series, I invited a therapist to come once a week, knowing that sharing their story might impact them psychologically. She would spend time talking with the women and conducting therapeutic workshops.

EB. Dignity, respect, or honour can be exuded through a photograph, but there are limitations to our medium. So, we have to start thinking about other mediums which can assist in filling those gaps. It could be creating an installation, integrating video, audio or text, etc. It is difficult to show everything that went on behind the scenes in a single image. You can only hope, in the end, that the people in the photo felt respected in the process.

AB. I relate to this comment about photography being a flawed medium. Photojournalism especially has a tendency of being a bit grandiose about what it is or what it can do. Acknowledging the limits of the literal box we’re in is much more honest and opens up the door to making better work.

KS. I relate to that as well. When I show the large-scale tintypes portrait of Indigenous women and non-binary people in galleries, I also include a voice recording of them. Often I feel that we’re neither seen or heard. Therefore, using both visuals and audio provides visibility and a voice.

SM. One aspect that I found particularly frustrating over the years, especially in documentary photography, is that the subjects are predominantly from disenfranchised community. I believe that happens because they are ‘easier’ to photograph. They’re easy prey. They have no defenses against the media. The middle class, who is hyper aware of the media, is much harder to access. So, we default to the ‘easier’ targets and then use the veneer of dignity as a justification for picking on them. Embedding oneself within a community for any length of time and gaining someone’s trust doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re representing them with dignity.

Kierra and Kayla. Photo by Endia Beal from "Am I What You're Looking For"

Dominica. Photo by Endia Beal from "Am I What You're Looking For"

There is this undeniable strangeness about entering people’s world, especially when it’s a particularly difficult time.

ATL. The opening paragraph of “The Journalist and the Murderer” by Janet Malcom, can apply to photojournalism and any act of representation. It goes: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse. Like the credulous widow who wakes up one day to find the charming young man and all her savings gone, so the consenting subject of a piece of nonfiction writing learns —when the article or book appears— his hard lesson. Journalists justify their treachery in various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about freedom of speech and “the public’s right to know”; the least talented talk about Art; the seemliest murmur about earning a living.”

While it doesn’t entirely reflects my opinion on non-fiction storytelling, it’s a damning but worth considering cynical perception of what I, we, do.

AB. The quote that you just read had me wondering how everybody justifies this practice? There is this undeniable strangeness about entering people’s world, especially when it’s a particularly difficult time. What I’m considering is that we all have a very fundamental human need to be seen, and that a lot of people in this world feel invisible. So when working on a story, I found that people, time and time again respond positively to having a witness who says: ‘I see you, I see what you’re trying to do, what you’re struggling with’. What I find difficult is sharing that relationship, that experience with a wider audience.

It’s not about the dignity of the people represented, but eventually that of the photographer who in this case was prepared to say ‘this is who I am’.

SM. My framework is honesty, which doesn’t always mean pretty. An example of that is Martin Parr’s work on Brighton Beach. He was chastised for being a white male snob. The transparency of his gaze as a curious outsider is singular and what makes the work brilliant is its honesty. He didn’t shy away from who he is, his perspective is that of a white male middle class person in England. It’s not about the dignity of the people represented, but eventually that of the photographer who in this case was prepared to say ‘this is who I am’.

KS. I can relate to what both of you are saying. Once, when I was photographing a friend I ended up highlighting her hands because she’s lived a long hard life and her hands show that. When we were done making the photograph together she said ‘you reminded me that beauty isn’t pretty, it’s empowerment and strength”. That moment of making her feel good about herself and represented accurately and honestly, that’s what I’m aiming for.

LBR. Given what we’ve discussed so far, what do you feel are some of the approaches and practices in photography, whether documentary or artistic, that need to be revisited in order for photographers to do a better job at representing people honestly and with respect?

BD. We need to think about our responsibility when publishing images and making someone’s image public. We have to think on the impact it will have in someone life.

ATL. I agree completely Bénédicte. And, one thing we have yet to touch on is thinking about the role of those who commission and funds our work and how their views on respect and how to honour people’s dignity might influence our projects. Even when somebody else isn’t dictating the parameters, I find myself unconsciously thinking about what I think people might want to see.

EB. Who’s commissioning is an important question, since they often have their own ideas about what the images might or should look like. Part of our responsibilities is to think about innovative ways to approach a story or a community, to take risks.

KS. Speaking about commissioning, there’s also a responsibility to make an effort to hire people from the communities who are able to challenge the way they have been shown up until now.

SM. I’ve been waiting for this time where everything gets torn up, reconsidered and reimagined. Part of the problem is that we have defined ourselves as story-tellers. Now, thanks to social media and other formats, photography is not so much a telling, but, more and more, a conversation. That changes everything.

Amber Bracken‘s interest is in the intersection of photography, journalism and public service with a special focus on issues affecting Indigenous people. With the rise of movements like Idle No More, communities are increasingly empowered to fight for a more just relationship with the government and non-native people. She is looking for ways to represent and foster that strength while documenting issues around culture, environment and the effects of inter generational trauma from colonialism.

Bénédicte Desrus is a french documentary photographer based in Mexico City represented by Sipa Press USA. She focuses on humanitarian and social issues around the world. Her photography explores the lives of people ostracized by society, and the communities they form to survive and find respect. She often spends months with her subjects. Recent stories explored the lives of elderly sex workers living in a shelter in Mexico City, Prader-Willy syndrome in Mexico, Donovan Tavera – Mexico’s only government-certified forensic cleaner, the anti-gay bill & persecution of homosexuality in Uganda, the albinos killing in Tanzania and global obesity.

Anastasia Taylor-Lind is an English/Swedish photojournalist who has been working for leading editorial publications all over the world on issues relating to women, population and war for a decade. She is a Harvard Nieman Fellow 2016, TED fellow ad National Geographic contributor.

Endia Beal is a North Carolina based artist, who is internationally known for her photographic narratives and video testimonies that examine the personal, yet contemporary stories of marginalized communities and individuals. Beal currently serves as the Director of Diggs Gallery at Winston-Salem State University and Associate Professor of Art.

Stephen Mayes is Executive Director of the Tim Hetherington Trust. For over 25 years, he has managed the work and careers of top-level photographers at VII, Network Photographers, EyeStorm, and Art+Commerce, amongst others. He also served as Secretary to the World Press Photo from 2004 to 2012. He’s profoundly committed to reflecting and writing about the ethics and practice of photography.

Kali Spitzer, a trans disciplinary artist who mainly works with film, is Kaska Dena from Daylu (Lower Post, British Columbia) on her father’s side and Jewish from Transylvania, Romania on her mother’s side. She is from the Yukon and grew up on the West Coast of British Columbia in Canada on unceded Coast Salish Territory. At the age of 20, Kali moved back north to spend time with her Elders, and to learn how to hunt, fish, trap, tan moose and caribou hides and bead. Kali documents these practices with a sense of urgency, highlighting their vital cultural significance.

Laurence Butet-Roch, a member of the Boreal Collective and Muse Projects, is a freelance writer, photo editor, photographer and educator based in Toronto, Canada committed to encouraging critical visual thinking. Her words have appeared in the British Journal of Photography, The New York Times Lens Blog, TIME Lightbox, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Polka Magazine, PhotoLife, BlackFlash and Point of View. She is the editor of Flash Forward Flash Back.

The conversation continues!

If you’d like to add your voice, submit your response to our editor,

Laurence Butet-Roch at laurence@magentafoundation.org