Montreal-based photographer Matthew Brooks uses his 8x10 large format camera to create images that play with the viewer’s idea of reality. His work toys with our concept of the photograph as a document, destabilizing the divide between fact and fiction. In discussion with Fehn Foss, Brooks looks at where he is drawing his references from, where his practice began, and where it is going.

Published November 20, 2018

Photos by Matthew Brooks, 2017 Flash Forward Winner

FF. We met first year at Concordia in the BFA, Photography program and now you’re finishing your MFA there. How is your experience of Concordia going?

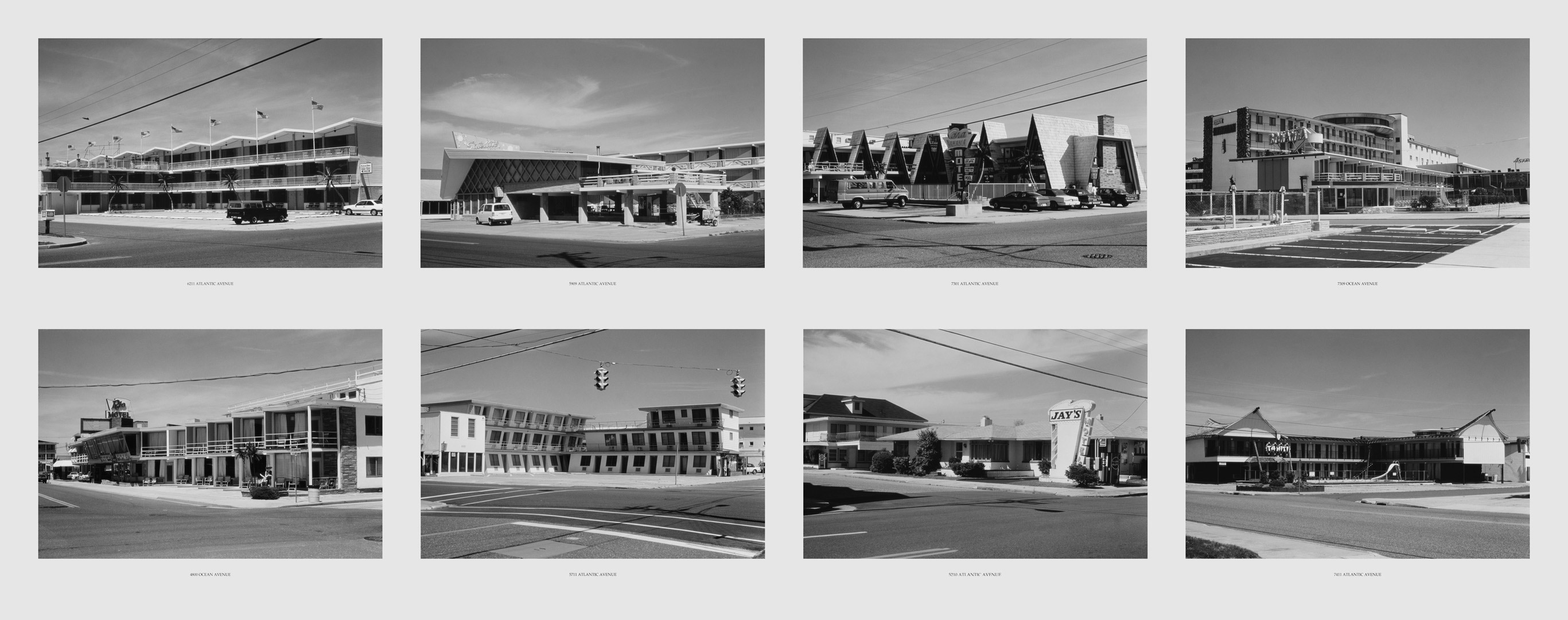

MB. Concordia has a great program: they have an expansive program and one of the few colour darkrooms left in the country, while other schools like Emily Carr closed their colour darkroom a while ago. In the first year of my BFA, I was coming from a place of scant knowledge: I did a bunch of weird work, but the images I made in Clara Gutsche’s class are oddly connected to what I’ve been doing in my MFA so far. I’m basically at the stage where I need to present my thesis within a year, to year and a half. I’m teaching this year as well. What I’m working on for my thesis is a body of work that focuses on Wildwood, NJ. There’s over 200 motels in only 3.6 square kilometres. Drawing on the rich iconography of the motel and its place in the histories of film and photography, the images in this body of work function both as documents of this fading architecture and moody cinematic tableaus, occupying a complex position between reality and fiction. The MFA program has been a more serious and intensive period of production where I’ve called into question and reworked my approach to making work. The reason I started the MFA program so soon after the BFA was because I was working so intensely as a research and production assistant—I was really embedded in the photo program and my work was advancing quickly—so it just made sense to move to the next step. The MFA and BFA programs at Concordia have most of the same strengths: extensive darkroom/production facilities and generous, dedicated faculty members. The MFA program has the benefit of gaining access to research facilities (see Post Image Cluster, postimage.hexagram.ca), more intensive seminar classes, and smaller studio classes (6 photo students admitted per year).

Water's Edge Resort, Wildwood (2018-)

Caribbean Motel, Wildwood (2018-)

Quebec Motel, Wildwood (2018-)

FF. Lynne Cohen’s work was shown to us in our first year of Concordia’s Photography program. Her practice focuses entirely on the interiors of institutions, classrooms, spas, and other spaces where people convene in groups (either for work or for pleasure). She never had any figures in her images and treated each man-made environment as though it were a set—does her work have a large impact on you?

MB. I love Cohen’s work—always have. I see her work as a formalist practice rather than a documentary practice—her work is colour, light, geometry. I haven’t been photographing indoors for quite a while though. Now, I am more interested in the Vancouver School, specifically, the way that Stan Douglas and Jeff Wall work: the way that the images are lit, the way that the image relates to us. Their images are so poised and perfect: unreal reality is the base of their concerns. Vikky Alexander and Ken Lum are also important to me. I think they’re often overlooked but just as important. I’ve heard Ken Lum speak a few times, he is a wonderful speaker and very fun. I’m interested in images that combine staged elements with documentary strategies to occupy the space between the document and the fictional image. Right now, I am using all natural light for outdoor images. Then I massage them in post-production to pull them away from reality. I shoot often at night because I can get images to look hyperreal just by using the natural light, which at that time is rather theatrical. Initially, out of necessity, I was shooting 4×5, but I recently sold my 4×5 camera to force myself to shoot only 8×10. The amount of hyperreality you can get out of it is just that much more. The images this larger format makes are impossibly slick and complicate any documentary references.

Eight Demolished Motels (for Ruscha), Wildwood (2018-)

FF. How did you go from shooting interiors to focusing on outdoor spaces?

MB. I ran out of material at a certain point. To gain access to specific interiors, you have to knock on doors to find new spaces. Eventually, I exhausted my network of people I could reach out to. Though I hope to return to photographing interiors in the future. More generally, I’ve been moving away from approaching the photograph as a tool for documentation. Still, I’m using those strategies to create something semi-fictional. The way that the images are composed remains documentary but the end result is a construction. The image I made for Capture Photography Festival in 2017, The Telephone Salesman, was done completely in the studio and I’ve been looking at that as a direction to head towards. The studio space is exciting because you can build walls and work with objects in a controlled way. The next project I am looking to do is a completely fabricated series, done on a sound stage, with actors. That said, I also want to continue to do location work. Images made on location bear traces of life, like a handwritten sign in a window. A personal touch is something you can’t really make in the studio in the same way as when you discover vignettes of human presence on location: they would be impossible to recreate. But also there is magic in making something from scratch, its alchemic and exciting to make something completely new. Both methods are productive.

The Telephone Salesman

Production Still 01, The Telephone Salesman (2017)

Production Still 02, The Telephone Salesman (2017)

FF. How did your upbringing in Winnipeg inform your creative output?

MB. Winnipeg is only one hour from the US border so it’s very American looking. I grew up within the city limits. The city is very sparse, it has a lot of aging architecture. Having left Winnipeg for Montreal, and traveling back there to visit family, I now have more of an appreciation for its look. During my childhood, being so close to North Dakota I’d go to Fargo and other cities to shop. My mother and I, we’d go there once or twice a year. Now when I visit my family, I do the same thing, but with the intention to photograph. Having seen all the Coen Brothers movies, I have fun working in the Fargo area. There’s such a cinematic quality to it, which is important to my work.

Rae and Jerry's, Scenes from an untitled film (2016–)

FF. Your images are beautiful but in a disturbing, uncomfortable way. What do you hope the viewer takes away from your work?

MB. One of the core concerns I’m playing with is authenticity. At the moment, in regards to images, we have no way to discern what is real and what is not. It is profoundly disturbing to think about the recent video and audio editing software that Adobe is developing, Project VoCo. These programs are getting so sophisticated, making it impossible to determine what is real and what’s been tampered with. And, we have politicians who refuse reality in so many ways. With my work, hopefully the viewer is going to ask what are the qualities of the images that make it believable or unbelievable. A lot of what I do in post-production is in Photoshop—trying to make the image look like what I saw. From there a set of problems arise: photographs have flaws, whether as a result of the film/sensor used, lenses, human error, etc. When you remove those flaws almost entirely, the image is actually a closer rendition to “reality” but as a result it looks less like a photograph since these flaws are actually how we’ve come to understand the qualities of photographs. For example, HDR photography often looks artificial even if it’s closer to the dynamic range that we can see with our eyes. That’s the paradox that I’m interested in: the closer the image resembles what our eye can see, the less it looks like a “real” photograph. The slick veneer of my work is meant to intrigue, to be seductive, like an ad. The polish draws you in and then you move past that to be more critical. Hopefully the more you think about it, the more the images become disturbing. The narratives they embody are rather dark, much like in the work of the Coen Brothers. The quality of the pictures suggests something happened before or after that isn’t necessarily wholesome. If you look at the work of Wim Wenders and cinematographer Robby Müller, especially their films The American Friend or Paris, Texas—that quality of light that they developed is totally in line with what I’m doing. My work has a similar mood: it’s not happy, it has a heaviness to it.

Dairi-Wip Drive-In, Scenes from an untitled film (2016–)

Meat Market, Scenes from an untitled film (2016–)

FF. Human presence makes itself known in your work because each space is one that humans use or frequent. However, framed family photos or images of people on posters are the only human figures within your images. What is your reasoning behind that?

MB. I am working towards adding people. In December 2017, I made a photograph at Westmount Square with an actor. For the work that I’m doing in Wildwood, NJ, I’d like to have some human figures in the compositions: to have some actors added into the tableaus to further fictionalize the town, to make it my own film set. I think images of people are interesting to us because we mirror what we see other humans doing and we are necessarily more intrigued by images containing human figures. That said, I don’t think that the images are devoid of human presence. Take Bob’s Oil Co; It has all these posters that add a human hand everywhere in it. There’s also a motorcycle parked, hinting that there was a person there recently.

Bob's Oil Co., Scenes from an untitled scenes (2016-)

FF. When you’re feeling burnt out, how do you recharge your creative energy?

MB. Because I’m teaching 210 [one of Concordia’s first year photography fundamentals courses] now, I don’t have a ton of downtime. Usually, I watch movies but it’s almost like work for me since I collect film stills and I’m watching analytically. But sometimes sitting down and working on my own images can feel peaceful and I am thankful that I can do that. I am thankful to have space to do something of my own volition. Most people can’t really say that they make anything, so we are lucky.

Morey's Pier, Wildwood (2018-)

FF. You definitely are busy balancing your academic pursuits, creative projects, and working with other artists. You are always up to something: how do you manage your time?

MB. I don’t balance them. The photos I make are so expensive to produce. From my first day at Concordia, I had to work all the time just to be able to shoot and print. The frames for the show at Ellen Gallery cost me nearly a year of rent. So, it’s a necessity to work all the time. Mostly I’ve been working with other artists. My obsession with perfection and skills in the digital space are useful to others, so I’ve had the great pleasure of working with artists such as Marisa Portolese, Adad Hannah, David K. Ross, and many others. I’ve worked for a ton of different people and that’s been super rewarding. I have my own studio now and I bought an industrial drum scanner, which I’m using to start a small business where I’ll be scanning film for myself and other artists as well. The equipment I need is so hard to get a hold of. I’ve been saving money since we met [five years ago] for a camera I bought last week. It’s a bit of an uphill battle.

Matthew Brooks is a Montreal-based artist originally from Winnipeg, MB, He holds a BFA in photography from Concordia University where he is currently and MFA candidate in Studio Arts. Aging architecture and material culture are frequent themes in his large-scale photographic work which explore the ambiguous narratives and the veracity of the image. Within his hyperreal tableaus, the viewer’s sense of the real is destabilized, creating an uncanny sense of both reality and fiction. He was named the 2017 recipient of the Lande Award in photography and the 2018 recipient of the Roloff Beny Foundation Fellowship. In 2017, he was awarded a SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Master’s and currently hold and FRQSC Master’s Research Scholarship.